Features

The Forgotten Story of the Expatriation Act

By Rachel Michelle Gunter

On April 10, 2025, the House of Representatives passed the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) Act on a largely party-line vote. Republicans hailed the bill as a way to safeguard American elections from undocumented migrants voting.

Critics, by contrast, warn it could make voting more difficult—if not impossible—for legally eligible voters. That’s especially true for tens of millions of married women, who may not be able to provide the required documentation to prove their citizenship to register to vote. Presenting a birth certificate remains the easiest way to do so under the Act. However, many married women take their husband’s surnames and therefore don’t have birth certificates that match their current legal names.

If the Senate passes the SAVE Act and President Donald Trump signs it into law, it will mean that millions of American women could find themselves in the shoes of Ethel Mackenzie, an early 20th century suffragist. Like McKenzie, they might see their ability to register and vote inhibited due to a congressional effort to prevent non-citizens from voting.

When Mackenzie tried to register to vote after California adopted woman suffrage in 1911, she was shocked to find out she couldn’t—despite being born in the Golden State. The culprit: the 1907 Expatriation Act, a federal law that stripped American women of their citizenship when they married non-citizens. Mackenzie’s case exposed how nativist policies could harm not just immigrants, but also the rights of American women. Now, the Save Act threatens to do the same.

In 1855, Congress passed the Naturalization Act. The law made any immigrant woman who married a citizen man into a citizen herself, as long as she met the racial requirements for citizenship. In 1868, the 14th Amendment established birthright citizenship for all people born in the U.S., except for American Indians and the children of foreign diplomats.

In the last three decades of the 19th century, however, nativist sentiment surged. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. In 1892, Congress extended and expanded the ban in the Geary Act. And in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated the Gentleman’s Agreement with Japan restricting Japanese immigration to the U.S.

That same year, the State Department pressured Congress to pass the Expatriation Act. Officials argued that marriages between citizens and non-citizens were handled differently by different nations and without a uniform rule in the U.S., the department couldn’t determine who was entitled to an American passport and protection while outside of the country.

Advocates for women’s suffrage thought the bill wasn’t a good idea and expected the courts to find it unconstitutional. They believed it was was wildly out of step with the ongoing erosion of coverture, a set of legal practices that the State Department had specifically used to justify their recommendation to Congress. Coverture derived from English common law and dictated that women suffered “civil death” upon marriage. They ceased to have a legal identity, and instead became covered by their husband’s legal identity. This left them unable to sign contracts or own property.

Suffragists fought to curtail coverture. But they also pushed another agenda item—one that helped propel the passage of the Expatriation Act—disfranchising non-citizens.

In the colonial era and the Early Republic, voting eligibility was often tied to property ownership and residency, rather than citizenship. As such, non-citizen voting was often legal and common. The practice surged again in the midwest in the 1830s, and was added to several state constitutions in the Deep South as a Reconstruction reform after the Civil War to counter the votes of unreconstructed white southerners.

But in the nativist climate of the early 20th century, the practice had fallen out of favor, and suffragists and other progressives fought to end it. Some suffragists argued that immigrants opposed suffrage for women and prohibition, and therefore immigrant voting posed a threat to their agenda. Reflecting how the two concepts became intertwined, South Dakota, Texas, and Arkansas put amendments on their ballots to enfranchise women while simultaneously ending non-citizen voting. The amendments passed in South Dakota and Arkansas.

As adoption of the Expatriation Act proved, the push to end non-citizen voting proved too powerful for suffragists to control. The new law made married women dependent citizens; their citizenship status was now entirely derived from that of their husbands.

When McKenzie discovered that the new law prevented her from voting, she filed suit, arguing that Congress could not take away by law what the Constitution granted her by birthright. While suffragists expected the courts would overturn the Expatriation Act, the nativist sentiments of the day were stronger than the trend towards women’s rights.

In 1915, the Supreme Court ruled against Mackenzie. As Ohio Representative John Cable summarized, the Court found that citizenship “was not such a right, privilege, or immunity that it could not be taken away by an act of Congress.” The justices found that Mackenzie’s decision to marry a non-citizen amounted to “voluntary expatriation.” She was now stateless and unprotected in her own country.

The decision left suffragists concerned that without married women’ independent citizenship, suffrage would be an impossibility.

Such fears proved wrong: in 1920 the ratification of the 19th Amendment prohibited states from barring women from voting on account of sex. Passage of the suffrage amendment encouraged Congress to revisit married women’s independent citizenship, because it meant that immigrant women naturalized through marriage could vote, while American women denaturalized by marriage were disfranchised. The League of Women Voters, formed out of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, lobbied Congress for married women’s independent citizenship.

In 1922, they scored a partial victory when Congress passed the Cable Act, which ended automatic denaturalization for American women if their spouse was an immigrant racially eligible for citizenship. The law also provided a pathway for denaturalized women to reclaim their citizenship. But it still excluded women who married Asian immigrants.

Some politicians used this period of denaturalization strategically to their own advantage. In 1928, Ruth Bryan Owen, daughter of William Jennings Bryan, became the first woman to win election to the U.S. House of Representatives from a former Confederate state. But upon her victory, her opponent sued arguing that her period of denaturalization after marrying a British serviceman during WWI meant that she hadn’t been a citizen for the previous seven years—a constitutional requirement to serve.

The challenge forced Owen, a native born citizen; daughter of a three-time presidential candidate, congressman, and Secretary of State; and a duly elected official from Florida to plead her case before Congress. Her fellow lawmakers chose to seat Owen, rejecting the challenge that threatened to undo the will of her constituents.

During the 1920s, Congress amended the Cable Act several times. Then, in 1933 the Senate voted to adopt the convention of the Pan American Conference, which argued that differences in nationality laws based on sex should be eliminated. The next year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Equal Nationality Act, through which American women achieved full, independent citizenship.

Sixty years later, a new round of concerns of undocumented migration prompted Congress to make it a crime for non-citizens to vote in federal elections. Lawmakers did so even though it hadn’t been legal for non-citizens to vote in either state or federal elections in any state since Arkansas’s ban went into effect in 1926.

Republicans allege that the SAVE Act will help enforce this existing law. But instead, it threatens to disenfranchise millions of married American women.

The law stipulates that people can prove citizenship either by presenting a REAL ID or a military identification card, if they confirm a person’s citizenship status. But many can not, which leaves people registering to vote with the option of presenting a state identification card or driver’s license in conjunction with a certified birth certificate that includes the “full name” of the applicant. It’s this last provision which poses a problem for up to 69 million women who took their husband’s name upon getting married. That means their birth certificates no longer include their full legal names.

The law makes no allowances for such situations. It does leave room for states to decide which secondary documents to accept, but this would still be an additional burden on married women, could be applied unevenly across the country, and may open the door for challenges to election results—like the one faced by Ruth Bryan Owen—on the grounds that states didn’t meet these onerous requirements.

A century after the suffrage movement, the SAVE Act threatens to echo the harms of the Expatriation Act. While it’s supporters claim it will target non-citizen voters, instead it could prevent American women from voting.

Analysis

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There are pains that refuse to be edited out of memory. No matter how carefully one chooses words, some experiences bleed through the page, heavy and unyielding. I write this not merely as a columnist accustomed to weighing public issues, but as a father whose pen now trembles under the weight of a personal loss that should never have happened.

The death of my eight-month-old daughter, Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman, is not just a private tragedy; it is a mirror held up to a system that looks impressive on the surface but collapses at the moment it is most needed.

On Friday, 23rd January 2026, my daughter was taken to General Hospital Suleja because she was unable to suck breast properly. It did not appear, at first, to be a death sentence. Like many parents, I trusted the judgment of trained professionals. The hospital itself inspired confidence. It is well renovated, neatly structured, and visually reassuring. From the outside, it looks like what a modern government hospital should look like. That appearance, in truth, persuaded me to use it. I believed, as any reasonable citizen would, that a facility that looks ready must surely be ready.

That belief became my greatest regret.

Rahmah was admitted the same day on the claim that her condition required emergency attention. She was taken into the Emergency Pediatric Unit, a designation that suggests urgency, speed, and competence. But what followed was neither urgent nor competent. For over thirteen hours, my daughter lay there in visible discomfort, struggling, crying faintly, weakening by the minute.

During this entire period, no doctor came to see her. The only available doctor was contacted several times by a Nurse. Calls were made. Messages were sent. Appeals were raised. Yet she never showed up, never examined the child, never intervened until she passed away Saturday night.

It is difficult to explain what it feels like to watch a child suffer while help remains just out of reach. Hospitals are supposed to be sanctuaries of hope, places where time matters and minutes are counted with seriousness. But in that Emergency Pediatric Unit in Suleja General Hospital, time became an enemy. Thirteen hours passed like a slow execution.

At some point, sensing danger, I requested that my daughter be transferred to a private hospital. I was ready to bear any cost. That request was not granted. Instead, oxygen was administered, as though oxygen alone could replace diagnosis, treatment, and medical presence. Oxygen became a gesture, not a solution. Sadly, when Rahmah took her last breath, it was not because her condition was incurable. It was because care was absent.

This is where the agony deepens. This was not a dilapidated structure abandoned by government. This was a renovated hospital, one that fits neatly into budget speeches and commissioning photographs. Niger State, since 2023, has consistently announced significant allocations to the health sector. In the 2024 fiscal year, over forty billion naira was earmarked for health, with emphasis on improving facilities, upgrading hospitals, and strengthening service delivery.

In 2025 and into the proposed 2026 budget, health allocations rose even higher, approaching over seventy billion naira, according to official budget presentations. These figures are not rumours; they are public records. They are read aloud in legislative chambers and celebrated in press releases. Yet, standing beside my dying child, those billions meant nothing.

A hospital is not healed by paint, tiles, and glass alone. A renovated building without doctors is like a body without a pulse. General Hospital Suleja may look functional, but inside, it suffers from a shortage that is far more dangerous than cracked walls. The absence of medical personnel, especially during emergencies, is a silent killer. No amount of renovation compensates for a system where doctors can choose not to respond to repeated calls when the needs arise.

Also strangely to me, there is the issue of power. What kind of hospital functions with generator power for barely three hours a day, typically between 8pm and 11pm? In a medical environment, power is not a convenience; it is life itself. Equipment depends on it. Monitoring depends on it. Emergency response depends on it. When power becomes a luxury, care becomes compromised. It is disturbing that in 2026, parents still have to pray for electricity in a government hospital while budgets worth billions are announced yearly.

What hurts most is not just the loss, but the realization that this suffering was avoidable. It was not fate. It was negligence. It was indifference. It was a system that has mastered the art of looking prepared while remaining dangerously hollow.

As a columnist, I have written about governance failures, policy gaps, and institutional decay. I have used statistics and official statements to interrogate power. But nothing prepares you for the moment when those abstract failures become personal. When the child you named, carried, and loved becomes a casualty of the same system you once critiqued from a distance.

I cannot, in good conscience, advise even my enemy to use that hospital again, not because it looks bad, but because looks deceive. The pain of trusting a fine exterior only to encounter fatal emptiness inside is something I would not wish on anyone. Health facilities should not be deceptive showpieces. They should be living systems, staffed, powered, responsive, and humane.

This is not a call for sympathy. It is a demand for honesty. If governments will continue to announce impressive budgets, then citizens deserve impressive outcomes. If hospitals are renovated, they must also be manned. If emergency units exist, they must function as emergencies, not waiting rooms for death. Accountability must move beyond paperwork and reach the ward, the night shift, the unanswered phone call.

Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman was eight months old. She was my only daughter. She deserved more than silence, more than delay, more than oxygen without care. She deserved a doctor who would show up.

Some losses change a man forever. This one has changed my writing. The pen is no longer just a tool of commentary; it is now an instrument of mourning and witness. If this column unsettles those who read it, then perhaps it is doing what hospitals like General Hospital Suleja failed to do that day — respond with urgency.

For my daughter, and for every child whose life depends on more than painted walls and budget speeches, this agony must be written, remembered, and acted upon.

Analysis

In Honour of Our Fallen Heroes, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

In Honour of Our Fallen Heroes, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Every nation is sustained by the quiet courage of those who stand between order and chaos. In Nigeria, that burden has rested heavily on the shoulders of the Armed Forces and other security personnel for decades, but especially in the past fifteen years of relentless insecurity. From the creeks of the Niger Delta to the forests of North West and North East to the highways of the North Central, Nigerian soldiers, airmen, sailors and policemen have borne the brunt of a war that is often unseen by those who sleep peacefully at night. To speak in honour of our fallen heroes is not merely to rehearse grief; it is to confront, honestly and courageously, the meaning of sacrifice, the demands of honour and the moral obligation of welfare owed to those who gave everything and to the families they left behind.

Nigeria’s contemporary security challenges did not begin yesterday. The Boko Haram insurgency, which escalated violently after 2009, has remained one of the deadliest conflicts on the African continent. According to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), tens of thousands of lives have been lost to the insurgency, with security personnel accounting for a significant proportion of the casualties. Names like Giwa Barracks, Baga, Monguno and Marte are etched into the collective memory of the military not just as locations, but as reminders of intense battles where many soldiers paid the supreme price. One such name that still resonates is Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Abu Ali, a gallant armoured corps officer who was killed in action on 4 November 2016 near Malam Fatori in Borno State while leading troops against Boko Haram fighters. His death symbolised the kind of front-line leadership that defines true military honour: commanding from the front, sharing risks with subordinates, and refusing the safety of distance.

Beyond the North East, the expanding frontiers of insecurity have claimed more lives. On 29 June 2022, Nigeria was shaken by the deadly ambush in Shiroro Local Government Area of Niger State, where at least 34 soldiers were killed by bandits while on a stabilisation mission. The scale of that single loss was a sobering reminder that the battlefield had shifted, and that sacrifice was no longer confined to one theatre of operation. Similar tragedies have followed. In March 2024, 17 soldiers lost their lives in Okuama community, Delta State, during a peace mission gone wrong, prompting national outrage and renewed debates about rules of engagement, intelligence failures and community-military relations. Each of these incidents added fresh names to a growing roll of honour, while also raising uncomfortable questions about preparedness, equipment and support for those sent into harm’s way.

Yet, sacrifice is not only measured in deaths. Thousands of Nigerian service personnel have returned from operations with life-altering injuries, trauma and scars that are invisible but enduring. The Defence Headquarters has repeatedly acknowledged the psychological toll of prolonged deployments, particularly in counter-insurgency operations where lines between combatants and civilians are blurred. The fallen heroes, therefore, represent not only those who died, but also those whose lives were irreversibly changed in service to the nation. To honour them meaningfully is to recognise that sacrifice is cumulative, personal and often lifelong.

Honour, however, must not be reduced to rhetoric. Every 15th of January, Nigeria observes Armed Forces Remembrance Day (now Armed Forces Celebration and Remembrance Day), a tradition rooted in the commemoration of soldiers who died in the First and Second World Wars and later expanded to include those lost in peacekeeping missions and internal security operations.

On 15 January 2026, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu through Vice President Kashim Shettima laid a wreath at the National Arcade in Abuja and reaffirmed the nation’s gratitude to its fallen heroes, describing them as “the pillars upon which our peace rests.” Similar ceremonies took place across states, from Lagos to Enugu, Kaduna to Kwara, accompanied by solemn words and military parades. These rituals matter. They reaffirm national memory and signal state recognition. But honour loses meaning if it ends at symbolism.

True honour is institutional and continuous. It is reflected in how promptly families of the fallen are informed, how respectfully remains are handled, how transparently benefits are processed and how consistently promises are kept. Over the years, allegations of delayed entitlements and neglected widows have surfaced, sometimes fuelling public anger and mistrust. The Nigerian Army and the Ministry of Defence have responded by clarifying welfare frameworks and insisting that official policies are robust. According to the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Defence, families of deceased service members are entitled to death benefits, gratuity, pensions, burial expenses and payments under the Group Life Insurance Scheme, a statutory policy that mandates life insurance coverage for all public servants, including military personnel.

In October 2023, President Tinubu approved an assurance policy valued at about ₦18 billion to cover life insurance benefits for fallen heroes, reinforcing the administration’s stated commitment to military welfare. In March 2024, the federal government also bestowed posthumous national honours on the 17 soldiers killed in Delta State, alongside promises of housing support and educational scholarships for their children. Several state governments have complemented federal efforts. Lagos State has sustained its scholarship scheme for children of fallen officers, while Ogun, Edo and other states have publicly pledged financial and social support to bereaved families during recent remembrance events.

These measures are commendable, and fairness demands that government be acknowledged where it has taken concrete steps. Welfare frameworks today are more clearly articulated than they were a decade ago, and there is greater public scrutiny of how military benefits are administered. Nonetheless, the test of honour lies not in policy documents but in lived experience. A widow who waits years for entitlements, or a child of a fallen soldier who drops out of school due to lack of support, represents a moral failure that no wreath-laying ceremony can erase. Honour must therefore be defended daily through efficient institutions, accountable processes and humane engagement with those who bear the cost of loss.

The argument for improved welfare is not sentimental; it is strategic. Nations that neglect the families of their fallen undermine morale among serving personnel. Soldiers who see that the state stands firmly by its promises fight with greater confidence and commitment. Conversely, perceived neglect breeds cynicism and erodes trust. Nigeria’s security challenges demand motivated, professional and resilient forces, and welfare is a critical pillar of that resilience. This is why calls by veterans’ groups, civil society organisations and commentators for continuous review of military welfare policies should not be dismissed as noise. They are part of a necessary civic conversation about national priorities.

There is also an ethical dimension that transcends strategy. The social contract between the state and its defenders is unique. When a citizen in uniform dies in service, the state inherits a moral responsibility to the dependants left behind. This responsibility does not expire with news cycles or budgetary constraints. It endures across administrations and economic fluctuations. In many ways, how a nation treats its fallen heroes’ families is a mirror of its values.

To be clear, honouring fallen heroes does not mean glorifying war or romanticising death. It means acknowledging the harsh realities of service and committing to reduce avoidable losses through better intelligence, equipment, training and leadership. It also means ensuring that when loss does occur, it is met with compassion, justice and sustained support. Sacrifice should never be cheapened by neglect, nor should honour be diluted by inconsistency.

As Nigeria continues to confront insecurity in multiple forms, the roll call of fallen heroes reminds us that peace is neither abstract nor free. It is paid for in blood, courage and broken families. To write in their honour is to insist that remembrance must translate into responsibility. The fallen cannot speak for themselves, but the living can speak through policies that work, institutions that care and a national conscience that refuses to forget. In doing so, Nigeria does not only honour its fallen heroes; it affirms the worth of every life pledged in defence of the nation.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

Analysis

Why Always Rivers State? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Why Always Rivers State? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Why is it always Rivers State? The question no longer sounds rhetorical. It has become a recurring reflection whenever Nigeria’s democracy appears strained, its institutions weakened, or its constitutional boundaries tested. Since the return to civil rule in 1999, Rivers State has repeatedly found itself at the centre of political crises that transcend ordinary electoral competition. What distinguishes Rivers is not merely the frequency of conflict, but the intensity, longevity and national implications of those crises. From succession battles to legislative breakdowns and federal intervention, the state has functioned as a pressure point where the contradictions of Nigerian democracy are most vividly exposed.

Rivers State’s peculiar trajectory cannot be understood without acknowledging its strategic importance within Nigeria’s political economy. As one of the core oil-producing states in the Niger Delta, Rivers hosts major petroleum assets that are critical to national revenue generation. Control of the state government therefore carries implications that extend far beyond its borders. Political office in Rivers confers access to enormous fiscal allocations, discretionary power over contracts and appointments, and leverage within national party structures. In a political system where state power is often personalised and monetised, such advantages raise the stakes of political competition to extraordinary levels.

From the onset of the Fourth Republic, these dynamics shaped the character of politics in Rivers. Peter Odili’s administration, which ran from 1999 to 2007, coincided with Nigeria’s democratic reawakening after prolonged military rule. His government helped stabilise civilian authority in the state and strengthened the Peoples Democratic Party’s dominance. Yet it also entrenched a culture of elite patronage that blurred the line between party loyalty and state ownership. Power became concentrated around the executive, while institutions that should have acted as counterweights remained weak. By the time Odili left office, Rivers politics had developed a reputation for fierce internal rivalry masked by outward party unity.

The crisis surrounding the 2007 governorship election revealed the fragility beneath that surface. Celestine Omehia’s short-lived tenure, terminated by a Supreme Court judgment that installed Chibuike Rotimi Amaechi on 25 October 2007, underscored how political outcomes in Rivers were increasingly determined by judicial intervention and party machinations rather than popular participation. While the court’s ruling was constitutionally grounded, it reinforced public perceptions that voters were peripheral actors in a system dominated by elite bargaining.

Amaechi’s eight years in office were among the most turbulent in the state’s history. Initially a key figure within the PDP, he later became a leading opposition voice against the party’s national leadership, particularly during the administration of President Goodluck Jonathan. His defection to the All Progressives Congress ahead of the 2015 elections transformed Rivers into a frontline state in Nigeria’s emerging two-party contest. Elections during this period were marked by violence, legal disputes and allegations of widespread irregularities. Rather than strengthening democratic norms, political competition in Rivers became increasingly militarised and litigious.

The ascension of Nyesom Wike to the governorship in 2015 represented both continuity and escalation. A former ally of Amaechi who became his fiercest rival, Wike governed with an assertive style that left little room for dissent. His administration pursued ambitious infrastructure projects and positioned Rivers as a visible development hub in the South-South. However, these achievements existed alongside an aggressive consolidation of political control. Party structures, legislative independence and local government autonomy were subordinated to the governor’s authority. Politics in Rivers became highly personalised, with loyalty to the executive serving as the principal currency of survival.

By the end of his second term in 2023, Wike had transcended state politics. His influence within the PDP and later his alignment with President Bola Tinubu elevated him into the national power equation. This context made the question of succession in Rivers unusually consequential. The emergence of Siminalayi Fubara as governor following the March 2023 election was widely interpreted as an extension of Wike’s political will. Fubara’s victory, secured with over 300,000 votes, appeared to confirm the durability of that arrangement.

Yet, Rivers’ history suggested that such successions are rarely seamless. Within months of assuming office, Fubara’s relationship with his predecessor deteriorated sharply. Disagreements over appointments, control of party structures and the autonomy of the executive quickly escalated. By October 2023, the conflict had spilled into the open, culminating in the burning of the Rivers State House of Assembly complex on 29 October. The symbolism of that event was unmistakable: the physical destruction of the legislature mirrored the collapse of constitutional order in the state.

What followed was an unprecedented institutional crisis. The Rivers State House of Assembly split into rival factions, each claiming legitimacy and producing contradictory resolutions. Impeachment proceedings were initiated and countered. Court orders multiplied, often conflicting, while governance ground to a halt. For months, Rivers effectively operated without a coherent legislative authority. This paralysis was not rooted in ideological disagreement or policy failure but in a struggle over political supremacy between a sitting governor and a former one determined to retain influence.

The depth of the crisis prompted federal intervention. On 18 March 2025, President Bola Tinubu declared a state of emergency in Rivers State, suspending the governor, his deputy and the entire House of Assembly for six months and appointing a sole administrator. The federal government cited political paralysis and threats to oil infrastructure, including incidents of pipeline vandalism, as justification. The National Assembly endorsed the proclamation, giving it legal force despite intense public debate.

This intervention marked a watershed moment in Nigeria’s post-1999 constitutional practice. Unlike previous emergency declarations, particularly the 2013 emergency in the northeast, the Rivers action involved the suspension of elected officials. Legal scholars and civil society organisations questioned its constitutional basis, noting that the 1999 Constitution outlines specific procedures for removing governors and legislators. The episode exposed unresolved ambiguities within Nigeria’s federal system and demonstrated how state-level political breakdowns can invite sweeping federal responses.

When the emergency rule was lifted in September 2025 and the suspended officials reinstated, Rivers returned to civilian governance, but the episode left enduring scars. Institutional credibility had been damaged, public confidence weakened and constitutional norms tested. The crisis projected the extent to which Rivers’ political instability had moved beyond internal party disputes to become a national concern.

The persistence of crisis in Rivers is not coincidental. It reflects structural weaknesses embedded within Nigeria’s democratic framework. The concentration of economic resources elevates political competition into a zero-sum contest. Godfatherism distorts succession, turning governance into a continuation of private power struggles. Political parties function less as democratic platforms and more as instruments of elite control. Legislatures and courts, rather than serving as independent arbiters, are drawn into factional battles. In such an environment, stability becomes fragile and crisis recurrent.

The consequences for governance are profound. Political paralysis disrupts budgetary processes, delays development projects and diverts attention from pressing social challenges. Despite its wealth, Rivers continues to struggle with unemployment, environmental degradation and infrastructural gaps. Citizens bear the cost of elite conflict through weakened service delivery and diminished trust in democratic institutions.

Why, then, does it always seem to be Rivers State? Because Rivers has become a concentrated expression of Nigeria’s unresolved democratic contradictions. It is a state where economic abundance coexists with institutional fragility, where political power is personalised, and where succession is treated as conquest rather than continuity. Until these underlying conditions change, Rivers will continue to oscillate between governance and crisis.

The lesson Rivers offers Nigeria is sobering. Democracy cannot be sustained by elections alone. Without strong institutions, internal party democracy and a political culture that respects constitutional boundaries, electoral victories become triggers for conflict rather than mandates for governance. Rivers State stands as a reminder that when politics is reduced to personal dominance, instability becomes inevitable. Until the structures that reward godfatherism and weaken institutions are dismantled, the question will persist, echoing across election cycles and administrations: why is it always Rivers State?

-

Analysis6 days ago

Analysis6 days agoThe Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

Analysis5 days ago

Analysis5 days agoNow That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

-

Diplomacy5 days ago

Diplomacy5 days agoCARICOM Raises Alarm Over Political Crisis in Haiti

-

News6 days ago

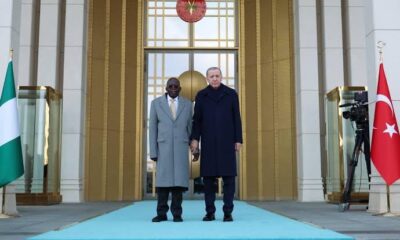

News6 days agoTinubu Unhurt After Brief Stumble at Turkey Reception

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMacron invites Chad’s Déby to Paris amid push to reset ties

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCourt, Congress Pile Pressure on DHS Over Minnesota Operations