Analysis

Are Forest Guards to the Rescue? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Are Forest Guards to the Rescue? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Nigeria’s insecurity story has become the longest‑running drama of our national life, and, at times, its most tragic one. Every week seems to bring another report of village raids, kidnappings, forest‑based ambushes or displaced families seeking refuge from bandits and terrorists. City centres barely register the scale of fear that grips the rural hinterland, where the reach of the state has, for years, thinned to near invisibility. In this context, one of the most talked‑about security interventions of 2025 has been the launch of Forest Guards, a new security force aimed at reclaiming Nigeria’s forest reserves from criminal exploitation. But the fundamental question remains: Is this initiative truly to the rescue?

On May 15, 2025, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu approved the establishment of a national Forest Guards system as part of broad efforts to curb escalating insecurity across Nigeria. The announcement, made at an expanded Federal Executive Council meeting, envisaged recruiting as many as 130,000 forest guards nationwide by directing each state and the Federal Capital Territory to hire between 2,000 and 5,000 operatives depending on their financial capacity. The recruitment and training process was to be jointly supervised by the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) and the Ministry of Environment, with other arms of government providing strategic partnerships.

Nigeria has 1,129 recognised forest reserves and protected areas spread across 36 states and the FCT, making it one of the countries with extensive forest cover on the continent. Many of these forests have become havens for bandits, terrorist groups and kidnappers who exploit the terrain’s complexity to evade the reach of conventional security forces. The initiative’s core premise is to deny these criminals the luxury of sanctuary and operational space by placing trained personnel directly within the forests and surrounding communities.

The launch was greeted with a blend of cautious optimism and scepticism. On one hand, the idea of forest‑specific security adherents — indigenous recruits familiar with local terrain — promised something more nuanced than the traditional military incursions that have repeatedly failed to sustain security gains. On the other hand, concerns about resourcing, coordination, recruitment delays and the overall viability of such a large force in a tilted fiscal climate began to surface almost immediately after the announcement.

Seven months after the launch, the first cohort of Forest Guards has begun to take shape. On December 27, 2025, over 7,000 newly trained Forest Guards graduated from an intensive three‑month training programme under the Presidential Forest Guards Initiative. The graduates emerged from exercises held simultaneously across seven frontline states — Borno, Sokoto, Yobe, Adamawa, Niger, Kwara and Kebbi — marking what many officials described as the operational takeoff of the project. These states were selected partly because they include forest corridors most closely linked to violent criminal activity.

At the graduation ceremonies, National Security Adviser Mallam Nuhu Ribadu outlined the initiative’s purpose: to “strengthen Nigeria’s internal security architecture by denying terrorists, bandits, kidnappers and other criminal groups sanctuary within forested and hard‑to‑reach terrains,” and to serve as “first responders, gather intelligence and support security agencies operating in forests and difficult terrain.” According to Ribadu, deployment would begin immediately, with salaries and allowances to commence without delay.

The guards were trained not simply in physical endurance and patrol discipline, but in human rights, international humanitarian law, ethics and civilian protection. This curriculum including arms handling and regulated use‑of‑force procedures was deliberately structured to ensure that the guards would operate professionally and within established legal frameworks.

Yet seven months after the presidential approval, not all states have fully embraced the initiative. As at last count, the recruitment efforts vary widely: while states like Borno, Adamawa, Kwara, Plateau, Niger, Edo, Anambra and Enugu have begun processes, others such as Kaduna, Ondo, Benue, Kano, Jigawa, Akwa Ibom and Gombe lag behind in recruitment and mobilisation. It was argued that without universal adoption and consistent funding, the force risks patchy coverage that does little to alter the country’s broader insecurity picture.

Still, the fact that thousands of guards are now equipped, trained and being dispatched to forest zones represents a symbolic break from past half‑measures. It reflects a growing consensus among policymakers and security strategists that conventional military responses, often reactive and episodic, must be complemented by specialised, sustained presence in the spaces where criminal networks thrive.

Nigeria’s approach echoes similar strategies elsewhere in the world, albeit adapted to local contexts. In southern Africa, anti‑poaching ranger units have shown that continuous, well‑trained presence in protected areas can significantly reduce illegal activity; documented declines in poaching and encroachment followed sustained ranger deployments in conservation zones. While Nigeria’s Forest Guards are focused on insecurity rather than wildlife protection, the operational logic is similar: constant presence alters the behavioural calculus of those who operate outside the law.

In India’s forested insurgency zones, forest guards working alongside conventional security forces have helped limit mobility and operational space for insurgent groups. The collaborative model, combining local knowledge, community engagement, and formal security mandates has been credited with improving early warning and preventive capacity in areas where terrain favours non‑state actors.

China, despite its very different political environment, has deployed millions of forest rangers nationwide to enforce laws and protect resources, underlying the broader principle that unmonitored terrain invites exploitation.

These international parallels suggest that a specialised force rooted in terrain familiarity and community engagement can yield positive results. But it also posits the prerequisites for such success: adequate resourcing, clear legal authority, accountability, consistent funding, and structures that prevent politicisation or fragmentation. Nigeria’s Forest Guards may be a promising model, but without these underpinning elements, they risk becoming another iteration of well‑meaning policy that struggles under real‑world pressures.

For rural communities long left to fend for themselves, the presence of Forest Guards is welcome. Anyone who has seen a village terrorised for weeks can attest to the psychological value of a sustained security presence. But analysts caution that security alone cannot provide a durable solution. Poverty, unemployment, weak local governance and distrust of the state remain powerful drivers of criminal recruitment and persistence. Unless Forest Guards are integrated into broader development strategies including livelihood support and meaningful local governance their impact may be limited to temporary disruptions rather than lasting peace.

Another dimension of the Forest Guards debate revolves around accountability and professionalism. Nigeria’s history with auxiliary forces and special initiatives has been mixed, with some units overstepping mandates or becoming politicised over time. For Forest Guards to be credible, they must operate transparently, with accountability mechanisms that reassure citizens and protect human rights. This is especially important in forest communities where distrust of security agents sometimes runs deep.

Effectiveness must also be measured, not assumed. Public discourse often gravitates toward dramatic figures and proclamations, but the real test will be quantifiable outcomes: reductions in forest‑based kidnappings, dismantling of criminal encampments, improved safety on rural routes, and greater confidence among farmers and traders in returning to their lands. Nigeria’s security sector has sometimes been weak on data‑driven evaluations, but if Forest Guards are to transcend rhetoric, clear metrics and regular reporting will be indispensable.

Sustainability remains the overbearing question. Maintaining a specialised force of potentially 130,000 personnel that is well trained, paid, monitored, and accountable requires serious budgetary commitment. Nigeria’s economy is under strain, and security spending already commands a significant share of public finances. Ensuring that Forest Guards do not become victims of fiscal neglect will require sustained political will that goes beyond headline launches.

Yet, even with these caveats, the emotion in many affected communities is unmistakable: cautious hope. For farmers whose fields have been overrun, for traders who abandoned routes for fear of kidnappers, and for families rebuilding after raids, the idea that state presence could transform once‑feared forests into safer spaces matters deeply. It may not be the single panacea for all forms of insecurity, but it is an acknowledgment that Nigeria’s security challenges demand innovative and context‑specific solutions.

Ultimately, whether Forest Guards are truly “to the rescue” will depend on actions taken in the months and years ahead, not only on the ground but in corridors of policy, budgeting and public accountability. The forests have waited long enough for effective governance; now, the state’s ability to sustain this initiative may be one of the defining tests of its commitment to protecting every Nigerian, not just those in urban centres.

Nigeria’s insecurity did not emerge overnight, and it will not vanish overnight. Forest Guards represent an important step toward recognising that the battle for peace includes the spaces that have long been ignored. If properly resourced, professionally guided, and integrated with broader security and socio‑economic frameworks, they may yet prove to be not just a policy experiment, but a genuine rescue for communities long overshadowed by fear.

Analysis

Savannah Shield and the Security Recalibration of Kwara State

Savannah Shield and the Security Recalibration of Kwara State

By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

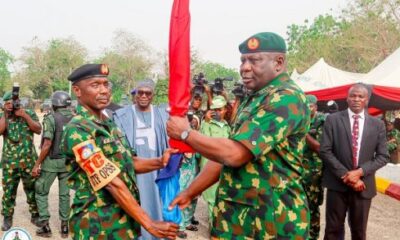

On Thursday, 19 February 2026, at the historic Sobi Barracks in Ilorin, Kwara State did more than launch a security operation. It signalled a recalibration. The formal flag-off of Operation Savannah Shield by Governor AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq alongside the Chief of Defence Staff, General Olufemi Oluyede, the Chief of Army Staff, Lieutenant General Waidi Shaibu, senior Nigerian Army commanders and heads of security agencies represented a strategic adjustment to a changing threat landscape.

Having covered Nigeria’s major military theatres for nearly a decade — from Operation Sharan Daji to Operation Accord and to Operation Sahel Sanity and now Hadarin Daji in the North-West to Operation Delta Safe in the South-South and Operation Safe Haven and Operation Whirl Stroke in the North-Central — I have come to understand that recalibration, not reaction, defines sustainable security. Savannah Shield is best understood within that framework: a preventive correction designed to interrupt an emerging trajectory before it hardens into crisis.

Kwara’s security story over the past two years has been one of gradual but undeniable pressure. Between 2024 and 2025, reported kidnapping incidents along the Ilorin–Jebba–Mokwa corridor and rural incursions in parts of Kaiama and Baruten Local Government Areas raised alarm within security circles. National crime tracking datasets and internal security briefings presented in Abuja in late 2025 reflected a broader pattern: North-Central Nigeria recorded an increase in abduction cases year-on-year, mirroring spillover effects from the North-West’s entrenched banditry networks.

Kwara was not yet a frontline theatre. But it was no longer peripheral. Geography partly explains the vulnerability. The state shares strategic boundaries with Niger State to the north and Kogi to the east, while expansive savannah woodland and forest belts — particularly near Kainji Lake — provide concealment corridors. In conflict reporting, terrain is destiny. In Zamfara, forests became staging grounds for bandits. In Kaduna, forest belts enabled mobile kidnapping cells. Kwara’s terrain, if left insufficiently policed, risked similar exploitation.

It is important to distinguish threat types accurately. Kwara is not contending with a large-scale ideological insurgency akin to Boko Haram’s campaign in Borno. The dominant security pattern has been criminal banditry — kidnapping for ransom, cattle rustling and sporadic attacks targeting vulnerable communities. Yet the distinction offers little comfort if criminal enclaves begin to entrench themselves. Across Nigeria, the line between economic criminality and violent extremism has proven porous when safe havens emerge.

Operation Savannah Shield therefore represents an anticipatory defence. Its structure reflects lessons from other theatres. Rather than a fragmented deployment, it integrates the Nigerian Army, Nigeria Police Force, Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps and intelligence services under coordinated planning. Area domination patrols, forest clearance missions and rapid-response operations are being conducted simultaneously with intelligence gathering and surveillance.

The February 19 launch was not ceremonial theatre. It followed months of consultation between the Kwara State Government and federal authorities. Governor AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq’s engagement with the Presidency and defence leadership secured additional military reinforcement. The visible presence of the Chief of Defence Staff at the launch conveyed federal seriousness — a signal that Kwara’s recalibration had national backing.

From a factual standpoint, the state government has not limited itself to rhetoric. In the 2025 fiscal cycle, budgetary allocations supporting security logistics were increased. Confirmed procurement of patrol vehicles and communication equipment enhanced operational mobility. Community policing initiatives were expanded, and liaison structures strengthened between security agencies and traditional institutions.

Mobility and intelligence are operational currencies. In Kaduna between 2021 and 2023, the integration of aerial surveillance and ground coordination under Operation Thunder Strike reduced high-profile highway kidnappings along key corridors. In Zamfara, initial fragmentation under Operation Hadarin Daji slowed results until unified command structures were enforced. Kwara appears to have internalised those lessons from inception.

Since the launch of Operation Savannah Shield, early field reports suggest measurable improvements in patrol visibility along previously vulnerable routes. Residents in parts of Kwara North have reported increased security presence compared with late 2025. Security officials privately confirm that sustained patrol cycles have disrupted criminal mobility patterns. While comprehensive operational statistics remain confidential for tactical reasons, the qualitative indicators point to stabilisation momentum.

But recalibration demands depth, not just deployment. The sustainability question looms large. Military offensives can suppress activity; lasting stability depends on institutional reinforcement. The Nigeria Police Force in Kwara must build intelligence capacity and data-driven crime mapping systems to assume long-term stabilisation roles once immediate military pressure reduces threat intensity.

In every theatre I have covered, gains proved fragile when civilian policing capacity lagged behind military success.

Judicial coordination is equally critical. Arrested suspects must face timely prosecution. Kaduna’s experience in strengthening prosecution processes between 2022 and 2023 offers a useful blueprint. Deterrence is anchored not merely in arrest numbers but in the certainty of consequence. Kwara’s Ministry of Justice must align operational tempo with judicial throughput.

Security recalibration also intersects with economic policy. Kwara’s northern agricultural belt contributes significantly to food production. When insecurity disrupts planting and harvesting cycles, economic ripple effects follow — affecting markets, employment and food inflation. By stabilising rural communities, Savannah Shield safeguards both livelihoods and macroeconomic resilience.

Inter-state coordination will determine whether recalibration endures. Criminal networks relocate under pressure. I observed this dynamic in the North-West, where offensives in one state displaced bandits into neighbouring territories. Kwara must institutionalise intelligence-sharing protocols with Niger, Kogi, Oyo and Osun to prevent displacement cycles. A shield is only as strong as its perimeter.

Public communication deserves commendation. Transparent advisories and engagement with community leaders have sustained trust. In conflict zones, misinformation amplifies fear and undermines operations. Kwara’s measured communication approach counters panic while reinforcing cooperation.

Of course, realism tempers optimism. Security operations demand sustained funding. Logistics, fuel, maintenance and personnel welfare cannot be episodic. If Savannah Shield is to remain effective beyond its launch phase, fiscal consistency must accompany strategic clarity.

Yet what distinguishes Savannah Shield is not perfection but intent backed by structure. The recalibration is evident in three dimensions: anticipatory deployment before escalation, integrated command rather than siloed action, and alignment between security and development policy.

From a regional lens, the significance is broader. North-Central Nigeria is a strategic hinge between insurgency-prone North-East and bandit-dominated North-West. Preventing entrenchment in relatively stable states like Kwara strengthens national security coherence. Savannah Shield contributes to that containment logic.

After nearly a decade reporting from Nigeria’s security corridors, I have learned that the most meaningful victories are incremental. They manifest in reopened schools, functioning markets and uninterrupted farming seasons. They are measured in the quiet return of routine.

Kwara’s recalibration signals an understanding that waiting invites escalation. Acting early reduces long-term cost — human and economic. The February 19 launch was therefore less about spectacle and more about strategic timing.

Savannah Shield is not a silver bullet. No operation is. But it is a structured assertion that Kwara will not surrender its harmony to creeping insecurity. It is a commitment that governance will adapt to emerging threats rather than deny them.

In a national landscape often fatigued by crisis headlines, Kwara’s approach offers a measured alternative: acknowledge vulnerability, mobilise partnership, invest in logistics, align institutions and communicate transparently.

Security recalibration is not merely about raising a shield. It is about strengthening the arm that holds it and reinforcing the society it protects. If sustained with discipline, institutional learning and inter-state cooperation, Savannah Shield can become more than an operation. It can become a model of preventive governance in North-Central Nigeria and beyond.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

Analysis

Who Is After Peter Obi? By Boniface Ihiasota

Who Is After Peter Obi? By Boniface Ihiasota

On Tuesday, 24 February 2026, political tensions in Edo State reached a striking and violent inflection point when gunmen opened fire in Benin City, attacking a gathering that included Peter Obi and other political figures. The former Labour Party presidential candidate, now a presidential aspirant under the African Democratic Congress (ADC), was at the centre of this incident at the home of former APC National Chairman Chief John Odigie‑Oyegun after a high‑profile event where Olumide Akpata joined the ADC.

Reports described armed men following Obi and his entourage from the ADC Secretariat to Odigie‑Oyegun’s residence, opening fire and riddling gates and vehicles with bullets in what has been described by party supporters as a failed assassination attempt. The leadership and supporters were forced to flee for safety as shots rang out, creating panic among residents. Security agencies had not issued an official statement by the time reports were published, and no arrests had been publicly confirmed. Obi’s media team and aides confirmed that he was safe following the attack.

The event was widely shared in video footage circulating on social media, showing the aftermath — damaged vehicles, bullet‑riddled gates, and stunned party members assessing the scene. In remarks made in footage after the attack, Obi himself condemned what had happened as a disturbing signal about the state of democracy in Nigeria. He pointed to the violence and questioned why political actors should be subjected to armed attacks, warning against the normalization of such threats in the political sphere.

This shocking incident did not happen without context. More than seven months earlier, in July 2025, Governor Monday Okpebholo of Edo State made public remarks that triggered widespread condemnation when he suggested that Obi should not step into Edo without prior notification or security clearance from his office. The governor said he could not guarantee Obi’s safety if he visited without such clearance, prompting lawyers, civil rights activists, and opposition figures to call the statement unconstitutional and a threat to a citizen’s right to freedom of movement.

Human rights lawyer Femi Falana, SAN, criticized the governor and urged him to retract what he described as a veiled threat to Obi’s life, citing constitutional protections for the right to life and freedom of movement. Critics argued that no state governor has the authority to condition a Nigerian citizen’s internal movement on approval from a state office.

Opposition voices and civil society organisations responded strongly at the time, describing the warnings as not just politically insensitive but constitutionally offensive. The ADC, the party of which Obi is now a leading figure, called the governor’s comments “disgraceful and undemocratic”, insisting that Obi, like any Nigerian, has the right to move freely within the country and meet with citizens in their own states without permission.

Within the context of these events, the attack on Tuesday has been seen by many observers as more than an isolated act of violence. It came at a moment when political alliances are shifting ahead of the 2027 general elections, with established politicians like Akpata defecting to the ADC alongside Obi and veteran political figures such as Odigie‑Oyegun. This shift signalled a growing challenge to the existing political order in Edo and raised the stakes of the contest for political influence in the region.

For Nigerians in the diaspora, who followed Obi’s political journey with hope for democratic reform and a departure from entrenched political structures, these developments have raised difficult questions. What does it mean for political competition in Nigeria when a leading opposition figure and senior statesmen are targeted with gunfire? How should democratic culture respond when political rhetoric — such as the warnings issued by a sitting governor — precedes real threats and violence in public life? The passage from heated words to actual shootings spells a larger concern about political space and intolerance.

The dynamics at play also reflect deeper anxieties about the freedom of opposition figures to participate in democratic politics without fear. If a state leader’s public statements are perceived as threats and then violence follows, the perception among citizens — both within Nigeria and abroad — is that democratic norms could be weakening rather than strengthening. The very idea of political engagement, debate and competition depends on a shared trust that differences in ideology and leadership transitions can be negotiated peacefully within the boundaries of law, not through intimidation or violence.

Yet there is another dimension to this story. In their defence, some officials have framed security concerns as legitimate in a country struggling with widespread insecurity challenges. The balancing of political freedom and personal safety is a real and complex issue in many parts of Nigeria. However, the public articulation of such concerns must be handled with extraordinary care so as not to undermine the constitutional rights of citizens or embolden those who might see anti‑democratic behavior as acceptable.

In the end, the question isn’t only who is after Peter Obi, but what set of political forces and behaviours are shaping the environment in which such episodes occur. The answer speaks not only to personalities, but to the evolving culture of Nigeria’s democracy — whether it remains open, inclusive, and protective of fundamental rights, or whether it concedes to intimidation, fear and exclusion.

For the diaspora watching, these events are a reminder that the struggle for democratic values is ongoing. It is a call to consider how political leadership, civic engagement, and the rule of law must be safeguarded so that no Nigerian — whether a former governor, presidential aspirant, or ordinary citizen — is left vulnerable for exercising their rights within their own country.

Analysis

Is Nasir El-Rufai on the Peril? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Is Nasir El-Rufai on the Peril? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There is something almost Shakespearean about the current phase of Nasir Ahmad El-Rufai’s political journey. Once firmly lodged within Nigeria’s innermost corridors of power, the former governor of Kaduna State now finds himself navigating choppy waters—estranged from elements of the establishment he helped midwife, locked in public disagreements with former allies, and increasingly defined by sharp media interventions rather than executive authority. The question therefore suggests itself with urgency: is Nasir El-Rufai on the peril, politically speaking, or merely repositioning for another audacious ascent?

To answer that, one must first understand the architecture of his rise. El-Rufai has always thrived at the intersection of intellect and insurgency. From his days as Director-General of the Bureau of Public Enterprises to his tenure as Minister of the Federal Capital Territory between 2003 and 2007, he cultivated the persona of a reformer unafraid of entrenched interests. In Abuja, he enforced the capital’s master plan with relentless precision, demolishing structures deemed illegal and digitising land administration through the Abuja Geographic Information System. Admirers saw courage; critics saw cold technocracy. But none doubted his influence.

His political resurrection after years in relative exile was equally strategic. As a central figure in the coalition that birthed the All Progressives Congress in 2013, El-Rufai demonstrated both tactical patience and elite networking. The APC’s 2015 victory was not merely a partisan turnover; it was a reconfiguration of Nigeria’s power map. In securing the governorship of Kaduna State that same year, El-Rufai transitioned from federal reform czar to subnational executive with a mandate to replicate structural transformation.

Kaduna was never going to be an easy laboratory. With its near parity of Muslim and Christian populations and a history of sectarian volatility, governance required not only administrative efficiency but also delicate social navigation. El-Rufai chose the path he knew best—structural reform. He implemented a Treasury Single Account to streamline finances, overhauled the civil service, and embarked on sweeping education reforms that culminated in the disengagement of more than 20,000 primary school teachers who failed competency tests. The state borrowed heavily for infrastructure, betting that long-term growth would justify short-term fiscal strain.

To his supporters, these were acts of bold leadership in a polity allergic to tough decisions. To his critics, they revealed a governor more comfortable with spreadsheets than sentiments. Southern Kaduna’s recurrent violence further complicated his record. His insistence on framing the crisis largely as criminality rather than ethno-religious persecution was analytically defensible in some respects, yet politically combustible. Perception hardened into distrust among segments of the population who felt unseen and unheard.

Even so, he secured re-election in 2019, proof that reform and controversy can coexist in Nigeria’s electoral calculus. But it was the transition from governor to elder statesman that has proven most perilous.

El-Rufai entered the 2023 political season as a visible ally of President Bola Tinubu during the APC primaries. His intellectual heft and northern pedigree positioned him as a bridge-builder within the party’s power arithmetic. When Tinubu won the presidency, many assumed El-Rufai would feature prominently in the new administration. His nomination as a minister appeared to confirm that trajectory until the Senate declined to confirm him, reportedly citing security concerns.

In Nigerian politics, symbolism often outweighs substance. The rejection was more than procedural; it signalled a rupture. For a politician accustomed to shaping events rather than reacting to them, the development marked a subtle but unmistakable shift from insider to outsider. Since then, his public commentary has grown more pointed. He has questioned the direction of the ruling party, hinted at betrayals, and portrayed himself as a custodian of principles sidelined by expediency.

Is this evidence of peril or repositioning?

There are at least three dimensions to consider. The first is institutional. El-Rufai no longer controls a state apparatus. Without the leverage of executive office, influence must be exerted through persuasion, coalition-building and narrative framing. This transition is difficult for leaders whose authority was reinforced by command structures. His recent media engagements which implies candid, combative and occasionally accusatory suggest a man recalibrating his tools.

The second dimension is relational. Politics is sustained by networks, and networks are sustained by trust. Reports of mistrusts between El-Rufai and key federal figures, as well as friction with his successor in Kaduna, complicate his positioning. In Kaduna, reviews of past contracts and policies have cast shadows backward, feeding narratives of vendetta on both sides. At the federal level, silence has often met his critiques, a strategy that can either isolate a critic or amplify him, depending on public mood.

The third dimension is strategic. Nigeria’s political elite operates in long cycles. Conversations about 2027 are already underway in quiet rooms. El-Rufai’s national profile, intellectual agility and northern base make him a potential factor in any future coalition calculus. His current dissent may therefore be less about grievance and more about differentiation—an effort to craft an identity distinct from a government facing economic and security headwinds.

Yet peril remains a real possibility. Nigeria’s political memory can be unforgiving. Leaders who overplay their hand risk alienation from both establishment and grassroots. If El-Rufai’s critiques are perceived as personal vendetta rather than principled dissent, his moral capital may erode. Moreover, the electorate has grown increasingly wary of elite quarrels that appear disconnected from everyday hardship. A politician who once sold reform as necessity must now demonstrate empathy as convincingly as efficiency.

Still, history suggests that El-Rufai has often converted adversity into opportunity. After leaving the Obasanjo administration under clouds of controversy, he returned stronger within a new coalition. After early resistance in Kaduna, he consolidated his authority and reshaped the state’s administrative culture. His career has been punctuated by phases of apparent crisis followed by strategic resurgence.

The deeper question may not be whether he is on the peril, but whether Nigeria’s political environment can accommodate his style of engagement. El-Rufai thrives on intellectual contestation and structural overhaul. He is less adept at the slow, conciliatory art of consensus politics. In a federation where legitimacy often rests on accommodation as much as achievement, this imbalance can be costly.

There is also the matter of narrative control. El-Rufai has long been his own chief spokesman, deploying social media and interviews with precision. In the absence of political office as he is currently, narrative becomes power. His recent outbursts once again keep him in the national conversation. Silence would have signified retreat.

So, is Nasir El-Rufai on the peril? The answer is layered. Institutionally, yes—he stands as an outsider in the power structure he once influenced. Relationally, yes—alliances appear strained and rivalries sharpened. Strategically, however, peril can be prelude. In politics, moments of vulnerability often precede recalibration and El-Rufai has always been a master of that.

Ultimately, El-Rufai’s future will hinge on whether he can transform dissent into constructive coalition-building. If he remains defined by grievance, the peril may deepen into isolation. If he channels critique into a broader vision that resonates beyond elite circles, the current turbulence could become a staging ground.

For now, he occupies an ambiguous space: not dethroned, not enthroned; neither silenced nor fully embraced. In that ambiguity lies both danger and possibility. Nasir El-Rufai has built a career on defying expectations. Whether this chapter marks decline or reinvention will depend less on his adversaries than on his capacity to balance conviction with conciliation.

The peril, if it exists, is not merely political. It is existential—the risk that a man defined by reform and combat may struggle in an era demanding reconciliation and breadth. But in Nigeria’s ever-shifting theatre of power, yesterday’s peril can become tomorrow’s platform.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoTrump Hails ‘Turnaround for the Ages’ in Record 110-Minute Address

-

Analysis3 days ago

Analysis3 days agoSavannah Shield and the Security Recalibration of Kwara State

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoMexico in Turmoil After CJNG Kingpin Killed in Military Operation

-

Analysis3 days ago

Analysis3 days agoWho Is After Peter Obi? By Boniface Ihiasota

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCARICOM Chair Engages Guyana in Fresh Push for Regional Integration

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoUK Court Hears Recordings in Diezani Bribery Trial