Health

Mpox Outbreak Spreads Across Central African Republic, Declares Emergency As Infections Reach Capital City

A rapidly spreading outbreak of the highly infectious mpox virus has reached the capital city of Bangui in the Central African Republic, prompting a state of emergency declaration by health officials. The outbreak, which was initially confined to rural areas, has now spread to the densely populated capital, increasing the risk of transmission between individuals.

Health Minister Pierre Somse warned that the risk of transmission is now very high, citing the densely populated nature of Bangui. Somse also expressed concerns that stigma surrounding the disease is causing some families to hide infected relatives, further increasing the risk to others.

The Central African Republic is the latest country in the region to declare an outbreak, following recent detections in Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The new strain of the virus in DR Congo has an estimated death rate of 10%, with over 12,300 suspected cases and 479 deaths recorded in the first half of this year.

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, spreads through close contact, contaminated objects, and respiratory droplets, causing symptoms such as fever, muscle aches, and lesions across the body. If left untreated, the disease can be deadly.

The World Health Organization has warned of the rising cases of mpox in west and central Africa, with the continent experiencing a decades-long increase in infections. The 2022 global epidemic affected numerous countries, including Europe, Australia, and the US. As the situation continues to unfold, health officials are urging vigilance and prompt reporting of suspected cases to prevent further spread of the disease.

Analysis

Examining Nigeria’s Health System and Preventable Deaths, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Examining Nigeria’s Health System and Preventable Deaths, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

My last week’s column, ‘The Agony of a Columnist,’ was written from a place I never expected to occupy. It was not an attempt at catharsis, nor was it designed to elicit sympathy. It was simply an account of what happened when a citizen encountered the Nigerian healthcare system at its most critical moment and found it wanting. The death of my eight-month-old daughter occurred within a public hospital that, on paper, appeared functional. What followed exposed a gap between appearance and capacity that deserves closer scrutiny rather than sentiment.

This week’s column is broader. It is about structure, policy, and outcomes. It is about what the data says and what lived experience confirms about the state of healthcare delivery in Nigeria, a system that reflects not only underperformance but failure at its most consequential moments.

Considering another recent case that captured national attention, that of Ifunanya Lucy Nwangene, a 25-year-old Abuja-based singer who was bitten by a cobra in her home. She sought emergency care immediately, moving from one health facility to another, and struggled to obtain antivenom and appropriate treatment before it was too late.

Accounts vary on the specifics, but the tragedy is indisputable. Her death, amid circumstances that could have been preventable, echoes the avoidable loss of my own child and reflects the same systemic weaknesses that place ordinary citizens at risk every day. Reports indicate that approximately half of Nigerian hospitals lack the capacity to manage snakebite cases effectively and that nearly all facilities experience difficulties in administering antivenom, the only treatment recognized by the World Health Organization for venomous bites. Such deficits in treatment capacity, emergency response, essential medicines, and clinical training are not anomalies; they are the predictable outcome of chronic systemic weakness.

Nigeria’s healthcare system is structured across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. According to the latest facility registry data, there are roughly thirty-eight thousand six hundred forty-five operational health facilities nationwide, a figure that includes both public and private establishments, translating to approximately eleven facilities per one hundred thousand people in a population exceeding two hundred and twenty million. Primary care facilities account for nearly eighty-eight per cent of all facilities, secondary care roughly twelve per cent, and tertiary facilities less than one per cent.

On paper, the distribution seems extensive, but quantity does not equal quality or functionality. The majority of primary healthcare centers, which form the first line of defence, are unable to deliver essential services consistently due to shortages of trained personnel, drugs, water, power, and equipment. Only about twenty per cent of primary facilities are considered fully functional, leaving millions of Nigerians dependent on emergency care that is often delayed or unavailable.

Health outcomes are determined by human resources as much as infrastructure, yet Nigeria’s health workforce is severely strained. The doctor-to-population ratio remains well below the World Health Organization’s recommended threshold of one doctor per six hundred people, with practical estimates ranging from one doctor per four thousand to one per five thousand citizens, and some areas experiencing ratios as low as one per nine thousand eight hundred.

Nurses and midwives are similarly scarce and unevenly distributed, favoring urban centers over rural and peri-urban areas. Absenteeism and burnout are systemic risks exacerbated by poor remuneration, unsafe working conditions, and limited career progression. The migration of trained health professionals abroad not only represents a loss of public investment but reduces the system’s capacity to respond to emergencies, increasing the likelihood that predictable crises result in preventable deaths.

Funding is a primary driver of these gaps. Nigeria is a signatory to the 2001 Abuja Declaration, committing to allocate at least fifteen per cent of annual budgets to health, yet the highest allocation recorded in any year remains below six per cent. By comparison, global benchmarks suggest public health spending should constitute at least five per cent of GDP to achieve basic universal health coverage, while Nigeria currently allocates approximately half a per cent. Per capita health expenditure ranges between ten and fifteen US dollars annually, which is insufficient to ensure functional hospitals, reliable emergency response, or the availability of essential drugs and equipment.

The inadequacy of public funding shifts the burden to households. Out-of-pocket payments account for nearly seventy to seventy-five per cent of total health spending, meaning that patients and families finance care at the point of illness rather than through pooled systems. Less than ten per cent of Nigerians are covered by any functional health insurance, and coverage is largely limited to formal sector employment. As a result, families often delay care, ration treatment, or avoid facilities altogether until conditions deteriorate beyond recovery.

The human consequences of these systemic failures are evident in national health indicators. Nigeria continues to have one of the highest maternal mortality ratios in the world, exceeding eight hundred deaths per one hundred thousand live births, and accounts for approximately twenty per cent of global maternal deaths despite representing less than three per cent of the world population. Infant and under-five mortality remain high, with recent surveys showing roughly sixty-seven deaths per one thousand live births and one hundred and ten per one thousand respectively. Many of these deaths result not from rare or complex conditions but from the inability of the health system to provide timely, skilled intervention for preventable or manageable illnesses. Malaria, pneumonia, childbirth complications, and neonatal distress often escalate into fatalities that could have been avoided had emergency care been available, adequately staffed, and well-supplied.

Infrastructure alone does not solve the problem. Hospitals are renovated, equipment procured, and wards repainted, but functionality depends on staffing, reliable power, water, supply chains, and governance. Electricity supply is particularly critical, as hospitals depend on continuous power for monitoring, oxygen delivery, laboratory diagnostics, and refrigeration of vaccines and essential medicines. Yet many facilities rely on intermittent generators with uncertain fuel supply, leaving patients exposed to system failures that no renovation or new building can correct.

Primary healthcare centers, despite their numbers, are frequently unable to provide preventive and early intervention services, meaning that conditions that should be addressed at the community level escalate to secondary facilities that themselves are overstretched.

Accountability within the health system is diffuse. Budget allocations are announced, but utilization and outcomes are weakly monitored. Staffing requirements are often unmet, and enforcement is inconsistent. Failures rarely attract consequences proportional to their impact, leaving citizens, including vulnerable infants and young adults, to bear the cost. Hospitals are frequently evaluated on the wrong metrics, such as bed count or physical infrastructure, rather than whether care is actually delivered. Time-sensitive emergencies cannot wait for policy announcements or cosmetic compliance; delays and absenteeism in these circumstances are measured in lives lost.

Both my personal experience and the case of the young singer illustrate these realities. My daughter was taken to Suleja General Hospital where initial symptoms did not appear severe, yet she required urgent intervention. Medical review was delayed, oxygen was administered without a definitive diagnosis or treatment plan, and a requested transfer to another facility was not effected in time. In the singer’s case, urgent antivenom administration was critical to survival, yet the system’s gaps prevented timely care, and the result was fatal. These outcomes are not anomalies; they are predictable expressions of systemic failure.

Nigeria does not lack reform frameworks. Initiatives exist to revitalize primary healthcare, expand health insurance, and improve maternal and child health outcomes. Some interventions have produced measurable gains in targeted areas, but they remain uneven and insufficiently scaled, often undermined by governance failures and weak operational oversight. The result is a system that prioritizes form over function, presenting the appearance of readiness while leaving emergency response and routine care vulnerable to failure. The consequences are borne not by policy-makers or administrators, but by citizens whose lives hang in the balance.

The purpose of revisiting last week’s column is not to relive personal grief but to insist on institutional reflection. Every preventable death, whether of a child in a public hospital or a young adult succumbing to a snakebite or otherwise, represents a failure of policy, funding, and governance. Healthcare is not an area where delays, absenteeism, or cosmetic compliance can be absorbed without consequence. Systems either respond, or they fail. In Nigeria, the record shows repeated, predictable failures. Mortality data, budget analyses, facility assessments, and lived experience all converge to the same conclusion: when the health system is tested, it often cannot deliver.

The crisis is visible, documented, and persistent. Nigeria’s hospitals function intermittently, supply chains are fragile, essential medicines are inconsistently available, and health workers are overstretched. Until outcomes, rather than infrastructure announcements, become the primary measure of success, preventable deaths will continue.

Tragically, the cost is measured not only in statistics but in lives that could have been saved. My daughter’s loss was personal, and the death of Ifunanya Nwangene was public. Both expose the same reality: a healthcare system that cannot guarantee timely, competent response in emergencies is not merely underperforming; it is failing its most fundamental obligation.

The reality requires less rhetoric and more reform, less emphasis on appearances and more attention to function. Budget allocations must be credible and linked to measurable outcomes, staffing requirements must be enforced, essential medicines and equipment must be reliably supplied, and emergency systems must be consistently operational. Until these conditions are met, Nigeria will continue to produce tragic but predictable stories of lives lost to systemic weakness, and citizens will continue to confront a healthcare system that appears reassuring until it is tested at its most critical moments.

Health

WHO Raises Alarm as Global Cholera Deaths Surge by 50%

WHO Raises Alarm as Global Cholera Deaths Surge by 50%

The World Health Organization (WHO) has raised fresh concerns over the global cholera crisis, revealing that deaths from the disease rose sharply for the second year running, despite the availability of effective prevention and treatment options.

In its latest report released on September 12, 2025, the UN health agency disclosed that cholera cases grew by 5 percent in 2024 compared to the previous year, while fatalities spiked by a staggering 50 percent.

Officially, more than 6,000 deaths were recorded, although WHO warned that the actual toll could be far higher due to widespread underreporting.

The report underscores how a disease once regarded as both preventable and easily treatable is staging a deadly resurgence.

Sixty countries reported cases in 2024, up from 45 in 2023 — one of the widest global spreads seen in recent years.

Alarmingly, 98 percent of infections were concentrated in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, where fragile health systems, conflicts, and poor access to clean water have left millions vulnerable.

“This disease should not be killing people in the 21st century. We have the tools to prevent and treat cholera effectively,” WHO officials said, linking the resurgence to deeper challenges in sanitation, safe drinking water, and access to equitable healthcare.

The surge in cholera cases comes at a time when many countries are already grappling with overstretched health systems weighed down by other infectious diseases, humanitarian crises, and climate-related disasters.

Experts point to flooding, drought, and mass displacement as key factors creating fertile ground for fresh outbreaks.

WHO and public health experts are now urging urgent global investment in water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure, alongside broader vaccine coverage and stronger rapid response systems.

Without these interventions, the organisation warns, the deadly upward trend could persist through 2025 and beyond.

For millions of families, cholera is no longer a relic of the past. It has re-emerged as a present and escalating threat to global health security.

Health

African Health Ministers Adopt Landmark Framework to Tackle Oral Diseases

African Health Ministers Adopt Landmark Framework to Tackle Oral Diseases

African ministers of health have adopted a new regional framework aimed at accelerating action against oral health diseases, which affect about 42 per cent of the continent’s population.

The framework was endorsed on Tuesday at the 75th session of the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Committee for Africa in Lusaka, Zambia.

It sets ambitious targets, including ensuring that at least half of each country’s population has access to essential oral health services, a 10 per cent reduction in the prevalence of major oral diseases, and that by 2028, 60 per cent of African countries have national oral health policies backed by budgets and trained staff.

Also central to the plan is the integration of noma—a neglected but devastating disease—into national health strategies in at least 50 per cent of endemic countries.

“Oral diseases have been largely neglected, making them among the most prevalent in our region,” said Dr Mohamed Yakub Janabi, WHO Regional Director for Africa.

“Our efforts to address this threat need to be robust, concerted and sustained. The framework agreed today highlights the urgent need for countries to prioritize oral health, ensuring adequate financing, workforce and leadership through a more integrated people-centred approach.”

WHO says oral health must be treated as a key part of universal health coverage.

To that end, it has supported governments with technical expertise, training, and advocacy.

Recent milestones include the abolition of toothpaste tax in Mauritius to expand access to fluoride toothpaste, enrolment of more than 14,000 health workers in WHO oral health training, and progress in securing recognition of noma as a neglected tropical disease in 14 countries.

Senegal’s Health Minister, Ibrahima Sy, welcomed the framework, stressing his country’s commitment to tackling noma and other oral health challenges.

“Senegal has long recognized noma as a critical public health issue. We are committed to ensuring that we are at the forefront of protecting people against oral diseases through a multisectoral approach,” he said.

Despite the scale of the challenge, investment in oral health across the region remains low. In 2019, more than 70 per cent of African countries spent less than US$1 per capita on oral health, far below the global average of US$50.

Only four countries had national fluoride guidelines as of 2023, and the region continues to face a severe shortage of oral health professionals—just 3.7 per 100,000 people, compared to the 13.3 required to meet current service demand.

To close these gaps, the framework outlines five priority actions: strengthening leadership and financing, developing national oral health policies, integrating oral health into essential service packages, bridging workforce deficits through task-sharing, and improving access to medicines and disease surveillance.

Health ministers pledged to mobilize political will, domestic and external resources, and technical expertise to ensure the framework delivers tangible results for millions of Africans at risk of preventable oral diseases.

-

Analysis1 week ago

Analysis1 week agoThe Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

Analysis6 days ago

Analysis6 days agoNow That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

-

Diplomacy6 days ago

Diplomacy6 days agoCARICOM Raises Alarm Over Political Crisis in Haiti

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMacron invites Chad’s Déby to Paris amid push to reset ties

-

News7 days ago

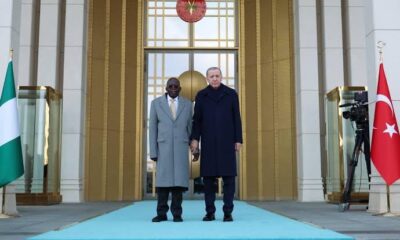

News7 days agoTinubu Unhurt After Brief Stumble at Turkey Reception

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCourt, Congress Pile Pressure on DHS Over Minnesota Operations