Analysis

World Bank Appoints Ndiamé Diop As New Country Director For Nigeria

The World Bank has announced the appointment of Dr. Ndiamé Diop as the new Country Director for Nigeria, succeeding Shubham Chaudhuri who has completed his term. Dr. Diop assumed his new position in Abuja on July 8, 2024, and is expected to lead the World Bank’s team in Nigeria, deepening policy dialogue and partnership with the government and key stakeholders.

Prior to his appointment, Dr. Diop served as the World Bank Country Director for Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand, based in Manila. During his tenure, he significantly increased the Bank’s financing to the Philippines,

more than tripling the support to advance critical economic reforms and bridge disparities in various sectors. He also supervised a large Malaysia-funded knowledge program aimed at helping the country become a high-income economy through cutting-edge economic analyses and technical assistance. Furthermore, he engaged the Thai government to resume World Bank investment lending after a pause of two decades.

Dr. Diop has held several leadership positions in the World Bank, including Head of the Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment unit for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, based in Jakarta and Bangkok, Lead Economist for Indonesia, Jordan, and Lebanon, and Country Economist roles in the Middle East and North Africa. He also served as the Bank’s Resident Representative for Tunisia between 2007 and 2010. Dr. Diop joined the World Bank in Washington DC in 2000 as a Young Professional.

As an accomplished economist, Dr. Diop has published extensively in peer-reviewed journals and books, focusing on fiscal policy and growth, monetary policy and inflation, macroeconomic policies, resilience to sudden stops in capital inflows, natural resource abundance, Dutch disease, and economic diversification.

In his new position, Dr. Diop will oversee the delivery and implementation of lending and non-lending support to Nigeria. He expressed his excitement about leading the World Bank’s program in Nigeria, especially at this critical time when Nigeria has a significant opportunity to make progress towards improving its economy and delivering development outcomes for its citizens. He looks forward to deepening the partnership with the Government of Nigeria at the Federal and state levels, ensuring quality technical and financial support that will help accelerate progress for Nigeria’s development priorities.

Dr. Diop emphasized that Nigeria is a dynamic and vibrant country that is significant for the entire sub-region. He reiterated the World Bank Group’s commitment to working with the government, development partners, and citizens to realize a thriving economy where jobs and economic prospects are created, and millions of Nigerians are lifted out of poverty.

The appointment of Dr. Ndiamé Diop as the new Country Director for Nigeria is a significant development in the World Bank’s efforts to support Nigeria’s economic growth and development. With his extensive experience and expertise, Dr. Diop is well-positioned to lead the World Bank’s team in Nigeria and make a positive impact on the country’s development priorities.

Analysis

Nigeria, the Coup Question and the Burden of History, by Boniface Ihiasota

Nigeria, the Coup Question and the Burden of History, by Boniface Ihiasota

For Nigerians in the diaspora, the confirmation of a foiled coup attempt against the administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu is both disturbing and deeply unsettling. It is the kind of news that instantly revives memories many hoped had been permanently buried—years of interrupted democratic journeys, military decrees, suspended freedoms and national stagnation. That the military high command has now acknowledged that some officers are under investigation for alleged plotting only reinforces a painful truth: democracy must be constantly guarded, even decades after its restoration.

Nigeria’s long encounter with military rule gives special gravity to any suggestion of unconstitutional ambition within the armed forces. From afar, where Nigeria’s progress is often measured against global democratic benchmarks, the very word “coup” carries an ugly resonance. It recalls an era when power was seized, not earned; when institutions were weakened rather than strengthened; and when ordinary citizens bore the brunt of elite recklessness. Against this background, the assurance by Defence Headquarters that implicated officers will face trial under the Armed Forces Act is appropriate and necessary. In a constitutional democracy, there can be no justification for mutiny, armed insurrection or any conduct that undermines civilian authority.

However, the handling of information surrounding this incident leaves much to be desired. Weeks of denial and silence before official confirmation created a vacuum quickly filled by rumours, speculation and anxiety. For Nigerians abroad—already sensitive to how instability at home affects the country’s image, investment prospects and diplomatic credibility—this lack of clarity was troubling. Transparency is not merely a public relations tool; it is a democratic responsibility. Investigations must be rigorous, evidence-driven and insulated from political interference if public confidence is to be restored.

It is equally important to draw a firm line between legitimate political opposition and criminal conduct. Democracies function on debate, dissent and accountability. Public criticism of government policies, especially amid rising economic pressures, does not amount to subversion. The Tinubu administration must therefore avoid politicising the matter or using it to blur the distinction between lawful opposition and professional misconduct within the armed forces. To do otherwise would risk eroding democratic norms in the name of protecting them.

The broader continental climate makes the situation even more delicate. Across parts of Africa, democratic reversals have become alarmingly frequent. Military takeovers in Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Chad—often justified by insecurity, economic hardship or governance failures—have reshaped the region’s political landscape. These developments explain why reports of a coup attempt in Nigeria last year triggered immediate concern. Nigeria is not just another country; it is a regional anchor. Any disruption to its democratic order would send shockwaves across West Africa and beyond.

From the diaspora perspective, a military intervention in Nigeria would represent a catastrophic setback. It would undo the gains of the past 26 years of uninterrupted civil rule and jeopardise the future of a country still striving to consolidate its democratic institutions. It would also complicate Nigeria’s international relationships, weaken investor confidence and further strain an already fragile economy. Above all, it would betray the expectations of millions of young Nigerians who have grown up under civilian government and demand better governance, not authoritarian detours.

The armed forces, therefore, must remain focused on their core constitutional duties. Nigeria is confronted by multiple security challenges: Boko Haram and ISWAP insurgencies, banditry, militancy and other forms of organised criminality. These threats require professionalism, discipline and unity—not political adventurism. Any internal distraction weakens the military’s capacity and emboldens non-state actors who thrive on instability.

Yet, responsibility does not rest with the military alone. History shows that while coups never offer lasting solutions, they often emerge in environments marked by economic distress, weak institutions and public disillusionment. From outside the country, where Nigerians observe governance systems that deliver basic services and social protection, the lesson is clear: leaders must be responsive and accountable. Addressing inflation, unemployment and poverty is not only an economic necessity; it is also a democratic imperative.

Equally important is the careful management of public communication. The military and the government must ensure that information relating to the alleged coup attempt is handled in a way that reassures citizens and investors alike. Alarmist narratives or vague statements risk portraying the state as fragile and insecure, which benefits neither democracy nor national cohesion.

Finally, the military high command must intensify efforts to shield its officers from civilian and political inducement. Coups rarely succeed without external encouragement. Officers must be constantly reminded of the grave consequences of unconstitutional actions and the primacy of national interest over personal ambition. At the same time, sustained funding, modern equipment and continuous training are essential to maintaining professionalism and morale within the ranks.

Analysis

Now That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

Now That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

In December 2025, Nigeria’s Senate confirmed Lateef Kayode Are as the ambassador-designate, only that where he will be posted to was unknown. Just a few days ago, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu through his spokesperson, Bayo Onanuga announced that he would be posted to the United States of America, ending a prolonged leadership vacuum across major Nigerian diplomatic missions.

For Nigerians living in the diaspora, particularly in the U.S., this development carries significant political, economic and strategic implications. The absence of a substantive ambassador in Washington, D.C., for more than two years had not only weakened Nigeria’s official voice in U.S. policy circles but also limited high-level advocacy on issues directly affecting Nigerians abroad—from visa policies to trade and investment ties.

Nigerians in the United States form one of the largest African-born communities in the country. Official data indicates roughly 393,000 foreign-born Nigerians reside in the U.S., making them one of the most educated and professionally active diaspora groups. Over 60 % hold bachelor’s degrees or higher, with many working in healthcare, technology, education and finance.

Other estimates suggest the broader Nigerian diaspora in the U.S. might be closer to 750,000 people, when including Nigeria-born and U.S.-born descendants who actively engage in both nations’ social, cultural and economic life. This community is not just a demographic cluster; it is a powerful reservoir of expertise and networks that can bridge the two countries.

Economically, the Nigerian diaspora plays a crucial role in Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings. In 2024, official remittances from Nigerians abroad reached $20.93 billion, more than four times the value of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the country during the same period. Such remittance flows are second only to crude oil in terms of foreign exchange inflow and accounted for a major stabilising support to Nigeria’s external accounts.

Given the scale of these flows, the Nigerian government and its diplomatic mission must pay greater attention to policies that make remitting easier, safer and more cost-effective. Recent discussions in the U.S. about proposed taxes on remittances to countries like Nigeria signalled potential challenges to these inflows, underlining the need for strong diplomatic engagement to protect economic interests.

In addition to remittances, U.S.–Nigeria bilateral trade remains robust, with total trade estimated at around $13 billion. This figure reflects deep economic interdependence—American energy firms, technology companies, and investors have interests in Nigeria’s energy and digital sectors, while Nigerian exports continue to find strong markets in the U.S.

Diplomacy is more than numbers. With a resident ambassador, Nigeria can more effectively advance strategic interests in areas such as education exchanges, technology partnerships, and security cooperation. The U.S.–Nigeria relationship already includes formal mechanisms like the U.S.–Nigeria Binational Commission (BNC) and the Commercial and Investment Dialogue, which cover development, governance, and economic opportunities.

A permanent ambassador strengthens Nigeria’s hand in these dialogues and ensures that policy decisions made in Washington reflect an accurate picture of Nigeria’s realities and priorities. This matters especially in areas like visa policies, professional mobility, and legal protections for Nigerians living and working in the U.S.

For many Nigerians living abroad, the practical functions of an embassy matter deeply—passport renewals, legal assistance, and consular support in times of crisis hinge on a mission that has the authority and clout to act. A long-standing absence of an ambassador meant that much of this work was handled by chargés d’affaires who lack the full mandate to negotiate broader policy solutions.

Having a full ambassador provides continuity, visibility, and influence. It reassures diasporans that their government cares about their welfare and is committed to protecting their rights and contributions in the host country.

Beyond services, the diaspora wants a Nigerian foreign policy that sees them as partners in development, not just sources of remittances or cultural ambassadors. Nigerians in the U.S. are entrepreneurs, researchers, policymakers, and educators who invest not just money but ideas back home. The new ambassador should leverage that intellectual capital and help create channels through which diaspora skills and networks can be systematically integrated into Nigeria’s economic and technological growth agenda.

Now that Nigeria has a U.S. ambassador-designate, it must shift from symbolic representation to strategic engagement. The ambassador must be visible, accessible and proactive—bringing diaspora voices into policy conversations, advocating for fair treatment of Nigerians abroad, and expanding economic and cultural ties that benefit both nations.

For the diaspora, this appointment is not just good news—it is an opportunity to deepen influence, strengthen identity, and build bridges that realize the promise of a more dynamic Nigeria on the world stage.

Analysis

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There are pains that refuse to be edited out of memory. No matter how carefully one chooses words, some experiences bleed through the page, heavy and unyielding. I write this not merely as a columnist accustomed to weighing public issues, but as a father whose pen now trembles under the weight of a personal loss that should never have happened.

The death of my eight-month-old daughter, Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman, is not just a private tragedy; it is a mirror held up to a system that looks impressive on the surface but collapses at the moment it is most needed.

On Friday, 23rd January 2026, my daughter was taken to General Hospital Suleja because she was unable to suck breast properly. It did not appear, at first, to be a death sentence. Like many parents, I trusted the judgment of trained professionals. The hospital itself inspired confidence. It is well renovated, neatly structured, and visually reassuring. From the outside, it looks like what a modern government hospital should look like. That appearance, in truth, persuaded me to use it. I believed, as any reasonable citizen would, that a facility that looks ready must surely be ready.

That belief became my greatest regret.

Rahmah was admitted the same day on the claim that her condition required emergency attention. She was taken into the Emergency Pediatric Unit, a designation that suggests urgency, speed, and competence. But what followed was neither urgent nor competent. For over thirteen hours, my daughter lay there in visible discomfort, struggling, crying faintly, weakening by the minute.

During this entire period, no doctor came to see her. The only available doctor was contacted several times by a Nurse. Calls were made. Messages were sent. Appeals were raised. Yet she never showed up, never examined the child, never intervened until she passed away Saturday night.

It is difficult to explain what it feels like to watch a child suffer while help remains just out of reach. Hospitals are supposed to be sanctuaries of hope, places where time matters and minutes are counted with seriousness. But in that Emergency Pediatric Unit in Suleja General Hospital, time became an enemy. Thirteen hours passed like a slow execution.

At some point, sensing danger, I requested that my daughter be transferred to a private hospital. I was ready to bear any cost. That request was not granted. Instead, oxygen was administered, as though oxygen alone could replace diagnosis, treatment, and medical presence. Oxygen became a gesture, not a solution. Sadly, when Rahmah took her last breath, it was not because her condition was incurable. It was because care was absent.

This is where the agony deepens. This was not a dilapidated structure abandoned by government. This was a renovated hospital, one that fits neatly into budget speeches and commissioning photographs. Niger State, since 2023, has consistently announced significant allocations to the health sector. In the 2024 fiscal year, over forty billion naira was earmarked for health, with emphasis on improving facilities, upgrading hospitals, and strengthening service delivery.

In 2025 and into the proposed 2026 budget, health allocations rose even higher, approaching over seventy billion naira, according to official budget presentations. These figures are not rumours; they are public records. They are read aloud in legislative chambers and celebrated in press releases. Yet, standing beside my dying child, those billions meant nothing.

A hospital is not healed by paint, tiles, and glass alone. A renovated building without doctors is like a body without a pulse. General Hospital Suleja may look functional, but inside, it suffers from a shortage that is far more dangerous than cracked walls. The absence of medical personnel, especially during emergencies, is a silent killer. No amount of renovation compensates for a system where doctors can choose not to respond to repeated calls when the needs arise.

Also strangely to me, there is the issue of power. What kind of hospital functions with generator power for barely three hours a day, typically between 8pm and 11pm? In a medical environment, power is not a convenience; it is life itself. Equipment depends on it. Monitoring depends on it. Emergency response depends on it. When power becomes a luxury, care becomes compromised. It is disturbing that in 2026, parents still have to pray for electricity in a government hospital while budgets worth billions are announced yearly.

What hurts most is not just the loss, but the realization that this suffering was avoidable. It was not fate. It was negligence. It was indifference. It was a system that has mastered the art of looking prepared while remaining dangerously hollow.

As a columnist, I have written about governance failures, policy gaps, and institutional decay. I have used statistics and official statements to interrogate power. But nothing prepares you for the moment when those abstract failures become personal. When the child you named, carried, and loved becomes a casualty of the same system you once critiqued from a distance.

I cannot, in good conscience, advise even my enemy to use that hospital again, not because it looks bad, but because looks deceive. The pain of trusting a fine exterior only to encounter fatal emptiness inside is something I would not wish on anyone. Health facilities should not be deceptive showpieces. They should be living systems, staffed, powered, responsive, and humane.

This is not a call for sympathy. It is a demand for honesty. If governments will continue to announce impressive budgets, then citizens deserve impressive outcomes. If hospitals are renovated, they must also be manned. If emergency units exist, they must function as emergencies, not waiting rooms for death. Accountability must move beyond paperwork and reach the ward, the night shift, the unanswered phone call.

Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman was eight months old. She was my only daughter. She deserved more than silence, more than delay, more than oxygen without care. She deserved a doctor who would show up.

Some losses change a man forever. This one has changed my writing. The pen is no longer just a tool of commentary; it is now an instrument of mourning and witness. If this column unsettles those who read it, then perhaps it is doing what hospitals like General Hospital Suleja failed to do that day — respond with urgency.

For my daughter, and for every child whose life depends on more than painted walls and budget speeches, this agony must be written, remembered, and acted upon.

-

Analysis1 week ago

Analysis1 week agoThe Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

Analysis6 days ago

Analysis6 days agoNow That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

-

Diplomacy6 days ago

Diplomacy6 days agoCARICOM Raises Alarm Over Political Crisis in Haiti

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMacron invites Chad’s Déby to Paris amid push to reset ties

-

News7 days ago

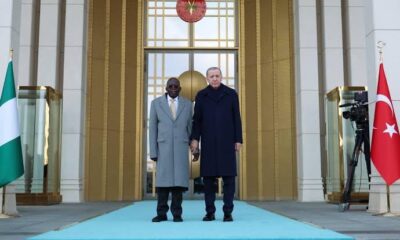

News7 days agoTinubu Unhurt After Brief Stumble at Turkey Reception

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCourt, Congress Pile Pressure on DHS Over Minnesota Operations