Opinion

The Cost Of Corruption: How Favoritism And Abuse Of Power Stifle African Development

In a recent revelation, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo exposed a near catastrophe that could have cost Nigeria its burgeoning telecommunications potential. He recounted how the transition from landline to mobile telephony nearly fell victim to corruption and favoritism under General Abdulsalami Abubakar’s leadership.

The proposed sale of a lucrative telecommunications deal for a mere $3 million—pennies compared to the $280 million ultimately realized—serves as a stark reminder of how systemic corruption undermines the development of African nations, which are rich in resources and potential.

Obasanjo’s narrative sheds light on a critical moment in Nigeria’s economic evolution. Prior to the mobile revolution, Nigeria was plagued by a lack of infrastructure, with millions waiting in vain for phone lines.

The impending sale of a vital telecommunications deal to cronies for a fraction of its worth exemplifies the rampant corruption that has historically thwarted progress. By intervening and opting for a transparent auction process, Obasanjo’s administration not only salvaged the deal but also fostered a competitive landscape that invited global telecom giants like MTN and Airtel into the Nigerian market.

This intervention catalyzed a sector that has since generated billions in revenue, illustrating how effective leadership can unlock opportunities that benefit the broader economy.

However, the shadow of corruption looms large, suggesting that such instances of progress remain exceptions rather than the rule. Corruption, favoritism, and abuse of office are not merely individual failings but systemic issues embedded within the governance structures of many African nations.

These practices have often diverted resources from essential public services, deterred foreign investment, and perpetuated cycles of poverty.

Countries with significant potential for economic growth are held back by the very leaders who are supposed to champion development. As Obasanjo pointed out, the “money to develop Nigeria is out there,” contingent on the establishment of a conducive and transparent business environment.

Yet, the reality is that corruption breeds distrust among investors and citizens alike, leading to an exodus of talent and capital. Without a robust framework for governance that emphasizes accountability and integrity, African nations risk stagnation, despite their rich resources and youthful populations.

To harness their full potential, African countries must confront and dismantle the structures of corruption. This involves implementing stringent anti-corruption laws, promoting transparency, and fostering a culture of accountability among public officials. Leaders must prioritize the creation of environments that not only attract foreign investment but also encourage local entrepreneurship.

Read also : How Corruption And Sabotage Are Suffocating Nigeria’s Petroleum Sector

Furthermore, the narrative of Nigeria’s telecom success should serve as a blueprint for other sectors. The potential for growth exists in agriculture, technology, and infrastructure, yet these opportunities will remain unrealized unless there is a commitment to ethical governance. The story of Nigeria’s telecommunications revolution is both a cautionary tale and a beacon of hope. It highlights how a single decision can pivot a nation from potential to prosperity, provided that integrity prevails over favoritism.

For African countries to truly unlock their potential, the path must be paved with transparency, accountability, and a steadfast commitment to serving the public good. Only then can the continent transform its vast resources into tangible benefits for all its citizens.

Analysis

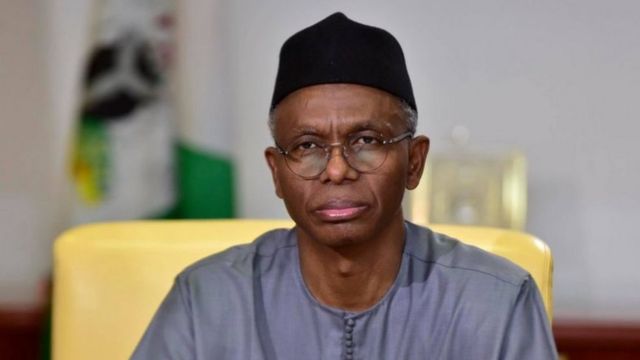

Is Nasir El-Rufai on the Peril? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Is Nasir El-Rufai on the Peril? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There is something almost Shakespearean about the current phase of Nasir Ahmad El-Rufai’s political journey. Once firmly lodged within Nigeria’s innermost corridors of power, the former governor of Kaduna State now finds himself navigating choppy waters—estranged from elements of the establishment he helped midwife, locked in public disagreements with former allies, and increasingly defined by sharp media interventions rather than executive authority. The question therefore suggests itself with urgency: is Nasir El-Rufai on the peril, politically speaking, or merely repositioning for another audacious ascent?

To answer that, one must first understand the architecture of his rise. El-Rufai has always thrived at the intersection of intellect and insurgency. From his days as Director-General of the Bureau of Public Enterprises to his tenure as Minister of the Federal Capital Territory between 2003 and 2007, he cultivated the persona of a reformer unafraid of entrenched interests. In Abuja, he enforced the capital’s master plan with relentless precision, demolishing structures deemed illegal and digitising land administration through the Abuja Geographic Information System. Admirers saw courage; critics saw cold technocracy. But none doubted his influence.

His political resurrection after years in relative exile was equally strategic. As a central figure in the coalition that birthed the All Progressives Congress in 2013, El-Rufai demonstrated both tactical patience and elite networking. The APC’s 2015 victory was not merely a partisan turnover; it was a reconfiguration of Nigeria’s power map. In securing the governorship of Kaduna State that same year, El-Rufai transitioned from federal reform czar to subnational executive with a mandate to replicate structural transformation.

Kaduna was never going to be an easy laboratory. With its near parity of Muslim and Christian populations and a history of sectarian volatility, governance required not only administrative efficiency but also delicate social navigation. El-Rufai chose the path he knew best—structural reform. He implemented a Treasury Single Account to streamline finances, overhauled the civil service, and embarked on sweeping education reforms that culminated in the disengagement of more than 20,000 primary school teachers who failed competency tests. The state borrowed heavily for infrastructure, betting that long-term growth would justify short-term fiscal strain.

To his supporters, these were acts of bold leadership in a polity allergic to tough decisions. To his critics, they revealed a governor more comfortable with spreadsheets than sentiments. Southern Kaduna’s recurrent violence further complicated his record. His insistence on framing the crisis largely as criminality rather than ethno-religious persecution was analytically defensible in some respects, yet politically combustible. Perception hardened into distrust among segments of the population who felt unseen and unheard.

Even so, he secured re-election in 2019, proof that reform and controversy can coexist in Nigeria’s electoral calculus. But it was the transition from governor to elder statesman that has proven most perilous.

El-Rufai entered the 2023 political season as a visible ally of President Bola Tinubu during the APC primaries. His intellectual heft and northern pedigree positioned him as a bridge-builder within the party’s power arithmetic. When Tinubu won the presidency, many assumed El-Rufai would feature prominently in the new administration. His nomination as a minister appeared to confirm that trajectory until the Senate declined to confirm him, reportedly citing security concerns.

In Nigerian politics, symbolism often outweighs substance. The rejection was more than procedural; it signalled a rupture. For a politician accustomed to shaping events rather than reacting to them, the development marked a subtle but unmistakable shift from insider to outsider. Since then, his public commentary has grown more pointed. He has questioned the direction of the ruling party, hinted at betrayals, and portrayed himself as a custodian of principles sidelined by expediency.

Is this evidence of peril or repositioning?

There are at least three dimensions to consider. The first is institutional. El-Rufai no longer controls a state apparatus. Without the leverage of executive office, influence must be exerted through persuasion, coalition-building and narrative framing. This transition is difficult for leaders whose authority was reinforced by command structures. His recent media engagements which implies candid, combative and occasionally accusatory suggest a man recalibrating his tools.

The second dimension is relational. Politics is sustained by networks, and networks are sustained by trust. Reports of mistrusts between El-Rufai and key federal figures, as well as friction with his successor in Kaduna, complicate his positioning. In Kaduna, reviews of past contracts and policies have cast shadows backward, feeding narratives of vendetta on both sides. At the federal level, silence has often met his critiques, a strategy that can either isolate a critic or amplify him, depending on public mood.

The third dimension is strategic. Nigeria’s political elite operates in long cycles. Conversations about 2027 are already underway in quiet rooms. El-Rufai’s national profile, intellectual agility and northern base make him a potential factor in any future coalition calculus. His current dissent may therefore be less about grievance and more about differentiation—an effort to craft an identity distinct from a government facing economic and security headwinds.

Yet peril remains a real possibility. Nigeria’s political memory can be unforgiving. Leaders who overplay their hand risk alienation from both establishment and grassroots. If El-Rufai’s critiques are perceived as personal vendetta rather than principled dissent, his moral capital may erode. Moreover, the electorate has grown increasingly wary of elite quarrels that appear disconnected from everyday hardship. A politician who once sold reform as necessity must now demonstrate empathy as convincingly as efficiency.

Still, history suggests that El-Rufai has often converted adversity into opportunity. After leaving the Obasanjo administration under clouds of controversy, he returned stronger within a new coalition. After early resistance in Kaduna, he consolidated his authority and reshaped the state’s administrative culture. His career has been punctuated by phases of apparent crisis followed by strategic resurgence.

The deeper question may not be whether he is on the peril, but whether Nigeria’s political environment can accommodate his style of engagement. El-Rufai thrives on intellectual contestation and structural overhaul. He is less adept at the slow, conciliatory art of consensus politics. In a federation where legitimacy often rests on accommodation as much as achievement, this imbalance can be costly.

There is also the matter of narrative control. El-Rufai has long been his own chief spokesman, deploying social media and interviews with precision. In the absence of political office as he is currently, narrative becomes power. His recent outbursts once again keep him in the national conversation. Silence would have signified retreat.

So, is Nasir El-Rufai on the peril? The answer is layered. Institutionally, yes—he stands as an outsider in the power structure he once influenced. Relationally, yes—alliances appear strained and rivalries sharpened. Strategically, however, peril can be prelude. In politics, moments of vulnerability often precede recalibration and El-Rufai has always been a master of that.

Ultimately, El-Rufai’s future will hinge on whether he can transform dissent into constructive coalition-building. If he remains defined by grievance, the peril may deepen into isolation. If he channels critique into a broader vision that resonates beyond elite circles, the current turbulence could become a staging ground.

For now, he occupies an ambiguous space: not dethroned, not enthroned; neither silenced nor fully embraced. In that ambiguity lies both danger and possibility. Nasir El-Rufai has built a career on defying expectations. Whether this chapter marks decline or reinvention will depend less on his adversaries than on his capacity to balance conviction with conciliation.

The peril, if it exists, is not merely political. It is existential—the risk that a man defined by reform and combat may struggle in an era demanding reconciliation and breadth. But in Nigeria’s ever-shifting theatre of power, yesterday’s peril can become tomorrow’s platform.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

Analysis

The Electoral Act and the Crisis of Electoral Confidence, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

The Electoral Act and the Crisis of Electoral Confidence, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Nigeria’s electoral laws have always mirrored the country’s uneasy relationship with democracy itself: hopeful in intention, fragile in execution, and controversial in outcome.

From the annulled June 12, 1993 election to the disputed polls of 2003, 2007, 2019 and, more recently, 2023, electoral legislation has remained both a tool of reform and a battlefield of political interest. The Electoral Act 2022, currently at the centre of renewed controversy, was enacted to correct decades of systemic flaws, but its implementation and the subsequent attempts to amend it have reopened old wounds about trust, transparency and the true commitment of Nigeria’s political elite to credible elections.

The Electoral Act 2022 replaced the Electoral Act 2010 (as amended), which had governed Nigeria’s elections for over a decade. The 2010 Act was widely criticised for being outdated in the face of evolving electoral manipulation techniques, weak in enforcing penalties for offences, and largely silent on the use of modern technology.

Between 1999 and 2019, election tribunals nullified hundreds of election results across all levels of government, presenting how deeply flawed the process had become. According to data from the National Judicial Council, more than 40 per cent of governorship elections conducted between 1999 and 2015 ended up in court, with several overturned. This pattern exposed the limits of electoral administration under existing laws and created an urgent demand for reform.

Against this background, the Electoral Act 2022 was introduced as a reformist statute designed to restore confidence in Nigeria’s electoral process. It introduced innovations such as the legal backing for electronic accreditation of voters through the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS), the possibility of electronic transmission of results, stricter timelines for party primaries, clearer campaign finance limits, and stiffer penalties for certain electoral offences. For the first time, Nigerian electoral law appeared to acknowledge that technology could serve as a bulwark against manipulation rather than a threat to sovereignty.

Yet, even at birth, the Act was controversial. Section 84, which barred political appointees from voting or being voted for at party primaries unless they resigned their appointments, generated intense legal and political resistance. While reform advocates argued that it would curb abuse of state power during primaries, opponents saw it as discriminatory. The provision was eventually nullified by the courts, making a recurring weakness in Nigeria’s electoral reform efforts: ambitious laws that collide with entrenched political interests and constitutional ambiguities.

The controversy surrounding the Act deepened after the 2023 general elections. Although BVAS significantly reduced incidents of over-voting, with INEC reporting that accreditation figures matched votes cast in most polling units, the failure to consistently upload polling-unit results to the INEC Result Viewing Portal in real time ignited nationwide outrage. INEC blamed technical glitches and connectivity challenges, but many Nigerians interpreted the delay as evidence that old habits had merely adapted to new tools. According to observer reports by the European Union Election Observation Mission, while BVAS improved transparency at the polling unit level, the collation process remained vulnerable to manipulation, particularly where results were moved physically without immediate electronic verification.

It is within this climate of suspicion that the National Assembly’s recent attempts to amend the Electoral Act have drawn fierce public scrutiny. Central to the controversy is the issue of electronic transmission of results. The Act currently empowers INEC to determine the manner in which results are transmitted, a provision that reformers argue is too discretionary. Civil society organisations, opposition parties and segments of the electorate insist that mandatory electronic transmission from polling units should be explicitly stated in the law to eliminate human interference during collation. Their argument is rooted in history: most electoral fraud in Nigeria has occurred not at the polling unit, where party agents and observers are present, but during result collation at ward, local government and state levels.

Supporters of legislative discretion counter this argument by pointing to Nigeria’s uneven infrastructure. They note that, according to the Nigerian Communications Commission, broadband penetration stood at 43.71% as at December 2023,, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas. From this perspective, making electronic transmission mandatory without addressing connectivity and power supply challenges could disenfranchise voters in remote communities. This disparity between ideal reform and practical constraints lies at the heart of the Electoral Act debate.

Beyond technology, the Act also touches on the persistent problem of electoral offences. Vote-buying, ballot snatching and voter intimidation have become entrenched features of Nigeria’s elections. During the 2023 elections, Yiaga Africa documented widespread vote trading across several states, with prices reportedly ranging from ₦2,000 to ₦10,000 per vote. The Electoral Act prescribes fines and prison terms for such offences, yet enforcement remains weak. Nigeria has recorded very few convictions for electoral crimes since 1999, a fact acknowledged by INEC itself.

The implications of these legal controversies for future elections, particularly the 2027 general elections, are profound. Electoral credibility is not built on election day alone; it depends on clarity and stability of the legal framework long before ballots are printed. INEC is required by law to release its election timetable at least 360 days before a general election. Persistent uncertainty about the final shape of the Electoral Act complicates planning, procurement and training. It also increases the likelihood of pre-election litigation, which has already become a defining feature of Nigerian politics.

In the 2023 election cycle, INEC recorded over 1,200 pre-election cases, many of which stemmed from ambiguities in party primaries and candidate selection rules.

Public trust is another casualty of the ongoing controversy. Voter turnout in Nigeria has been declining steadily, dropping from about 69 per cent in 2003 to roughly 27 per cent in 2023, according to INEC figures. This decline reflects growing voter apathy driven by the perception that votes do not count. When electoral laws appear malleable or subject to political bargaining, they reinforce cynicism and disengagement. For a country where over 60 per cent of the population is under 30, sustaining such distrust poses long-term risks to democratic stability.

Still, it would be unfair to dismiss the Electoral Act 2022 as a failure. The Act represents the most comprehensive attempt at electoral reform Nigeria has undertaken since 1999. The legal recognition of technology in voter accreditation marked a decisive break from the past, and the reduction in over-voting during the 2023 elections is a measurable achievement.

The clearer timelines for party primaries and candidate nominations have also improved internal party discipline, even if enforcement remains inconsistent. Compared to elections conducted under the 2010 Act, the 2022 framework has narrowed some avenues for manipulation, even as it exposed others.

The negative side, however, lies in what the Act leaves unresolved. Ambiguity in critical areas creates room for discretion, and discretion in Nigeria’s electoral history has rarely favoured transparency. The absence of decisive enforcement mechanisms for electoral offences undermines deterrence. The tendency to amend election laws close to election seasons fuels suspicion that reforms are driven by immediate political calculations rather than long-term democratic consolidation.

Nigeria’s electoral journey is ultimately a reflection of its broader governance challenges. Laws alone cannot guarantee credible elections, but weak laws almost certainly guarantee flawed ones. The controversy surrounding the Electoral Act is therefore less about technical clauses and more about political will. Countries such as Ghana and Kenya, which have faced similar challenges, have shown that sustained reform, backed by enforcement and civic education, can gradually rebuild trust. Ghana’s consistent improvement in election credibility since 2000, for instance, has been supported by clear electoral rules and visible consequences for violations.

As Nigeria looks ahead to future elections, the Electoral Act remains a pivotal instrument. Whether it becomes a foundation for democratic consolidation or another missed opportunity depends on how sincerely it is implemented, clarified and respected.

Electoral reform is not an event but a process, and Nigeria is still very much in the middle of that process. What is at stake is not just the outcome of the next election, but the credibility of the democratic project itself. In that sense, the controversy over the Electoral Act is not a distraction from Nigeria’s democratic journey; it is the journey, unfolding in real time, with all its contradictions, hopes and unresolved questions.

Analysis

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There are pains that refuse to be edited out of memory. No matter how carefully one chooses words, some experiences bleed through the page, heavy and unyielding. I write this not merely as a columnist accustomed to weighing public issues, but as a father whose pen now trembles under the weight of a personal loss that should never have happened.

The death of my eight-month-old daughter, Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman, is not just a private tragedy; it is a mirror held up to a system that looks impressive on the surface but collapses at the moment it is most needed.

On Friday, 23rd January 2026, my daughter was taken to General Hospital Suleja because she was unable to suck breast properly. It did not appear, at first, to be a death sentence. Like many parents, I trusted the judgment of trained professionals. The hospital itself inspired confidence. It is well renovated, neatly structured, and visually reassuring. From the outside, it looks like what a modern government hospital should look like. That appearance, in truth, persuaded me to use it. I believed, as any reasonable citizen would, that a facility that looks ready must surely be ready.

That belief became my greatest regret.

Rahmah was admitted the same day on the claim that her condition required emergency attention. She was taken into the Emergency Pediatric Unit, a designation that suggests urgency, speed, and competence. But what followed was neither urgent nor competent. For over thirteen hours, my daughter lay there in visible discomfort, struggling, crying faintly, weakening by the minute.

During this entire period, no doctor came to see her. The only available doctor was contacted several times by a Nurse. Calls were made. Messages were sent. Appeals were raised. Yet she never showed up, never examined the child, never intervened until she passed away Saturday night.

It is difficult to explain what it feels like to watch a child suffer while help remains just out of reach. Hospitals are supposed to be sanctuaries of hope, places where time matters and minutes are counted with seriousness. But in that Emergency Pediatric Unit in Suleja General Hospital, time became an enemy. Thirteen hours passed like a slow execution.

At some point, sensing danger, I requested that my daughter be transferred to a private hospital. I was ready to bear any cost. That request was not granted. Instead, oxygen was administered, as though oxygen alone could replace diagnosis, treatment, and medical presence. Oxygen became a gesture, not a solution. Sadly, when Rahmah took her last breath, it was not because her condition was incurable. It was because care was absent.

This is where the agony deepens. This was not a dilapidated structure abandoned by government. This was a renovated hospital, one that fits neatly into budget speeches and commissioning photographs. Niger State, since 2023, has consistently announced significant allocations to the health sector. In the 2024 fiscal year, over forty billion naira was earmarked for health, with emphasis on improving facilities, upgrading hospitals, and strengthening service delivery.

In 2025 and into the proposed 2026 budget, health allocations rose even higher, approaching over seventy billion naira, according to official budget presentations. These figures are not rumours; they are public records. They are read aloud in legislative chambers and celebrated in press releases. Yet, standing beside my dying child, those billions meant nothing.

A hospital is not healed by paint, tiles, and glass alone. A renovated building without doctors is like a body without a pulse. General Hospital Suleja may look functional, but inside, it suffers from a shortage that is far more dangerous than cracked walls. The absence of medical personnel, especially during emergencies, is a silent killer. No amount of renovation compensates for a system where doctors can choose not to respond to repeated calls when the needs arise.

Also strangely to me, there is the issue of power. What kind of hospital functions with generator power for barely three hours a day, typically between 8pm and 11pm? In a medical environment, power is not a convenience; it is life itself. Equipment depends on it. Monitoring depends on it. Emergency response depends on it. When power becomes a luxury, care becomes compromised. It is disturbing that in 2026, parents still have to pray for electricity in a government hospital while budgets worth billions are announced yearly.

What hurts most is not just the loss, but the realization that this suffering was avoidable. It was not fate. It was negligence. It was indifference. It was a system that has mastered the art of looking prepared while remaining dangerously hollow.

As a columnist, I have written about governance failures, policy gaps, and institutional decay. I have used statistics and official statements to interrogate power. But nothing prepares you for the moment when those abstract failures become personal. When the child you named, carried, and loved becomes a casualty of the same system you once critiqued from a distance.

I cannot, in good conscience, advise even my enemy to use that hospital again, not because it looks bad, but because looks deceive. The pain of trusting a fine exterior only to encounter fatal emptiness inside is something I would not wish on anyone. Health facilities should not be deceptive showpieces. They should be living systems, staffed, powered, responsive, and humane.

This is not a call for sympathy. It is a demand for honesty. If governments will continue to announce impressive budgets, then citizens deserve impressive outcomes. If hospitals are renovated, they must also be manned. If emergency units exist, they must function as emergencies, not waiting rooms for death. Accountability must move beyond paperwork and reach the ward, the night shift, the unanswered phone call.

Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman was eight months old. She was my only daughter. She deserved more than silence, more than delay, more than oxygen without care. She deserved a doctor who would show up.

Some losses change a man forever. This one has changed my writing. The pen is no longer just a tool of commentary; it is now an instrument of mourning and witness. If this column unsettles those who read it, then perhaps it is doing what hospitals like General Hospital Suleja failed to do that day — respond with urgency.

For my daughter, and for every child whose life depends on more than painted walls and budget speeches, this agony must be written, remembered, and acted upon.

-

Extra4 days ago

Extra4 days agoUS Veteran, Walter Obi Urges Compassionate Leadership at Valentine’s Event in US

-

Diaspora3 days ago

Diaspora3 days agoZenith Bank to Host Diaspora Engagement, Banking Services for Nigerians in Texas

-

Analysis4 days ago

Analysis4 days agoIs Nasir El-Rufai on the Peril? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoNigerian Govt Raises Alarm Over Illegal Recruitment of Its Citizens into Foreign Wars

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoA Home Worth Coming Back To: The Signature Residence by Mshel Homes

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoIran Claims Breakthrough on ‘Guiding Principles’ in Nuclear Talks with US