Diaspora

The Long American Tradition Of Categorizing Immigrants As Either Good Or Bad

The Long American Tradition Of Categorizing Immigrants As Either Good Or Bad

BY H I D E TA K A H I R O TA

In February, President Donald Trump’s Administration sent 178 Venezuelan migrants to the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. This is the latest chapter of the Trump Administration’s crackdown on immigrants, a project that officials have said will focus on those with records of unauthorized entry and violent crimes, or “the worst of the worst,” as Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem has put it. Advocates of strict border policing today typically divide noncitizens in the United States into two groups: regular immigrants and irregular (unauthorized) immigrants. Then, they disparage the latter as “illegal aliens” and call for their deportation.

This dichotomous categorization of immigrants is in part rooted in 19th century discourse on foreign-born workers, which divided them into “natural” and “unnatural” immigrants. Then as now, separating immigrants into clean binaries may reflect the ideological debates of the present moment, but seldom does doing so reflect the realities they are facing at that time. In the mid-19th century, some Americans criticized immigrant workers for threatening their employment by working at extremely low wages. U.S. workers’ opposition to immigrant labor became particularly strong during the 1870s and

1880s in response to the growth of

industrial capitalism after the Civil

War. At that time, U.S. workers suffered exploitative labor practices and the decline of wages, while the industrial and commercial elite enjoyed the extreme concentration of wealth. These situations provoked radical labor activism. Many labor leaders viewed immigrants employed by capitalists at low wages as advancing the unequal distribution of wealth and contributing to the impoverishment of U.S. workers.

Organized labor directed its harshest criticism against foreign contract workers, who were believed to be imported by capitalists as strikebreakers. Some employers did import immigrants as strikebreakers directly from Europe, but this practice was relatively rare. Many, if not most, foreign-born workers employed as strikebreakers immigrated to the U.S. on their own and were later hired by employers. Also, imported immigrants were not necessarily unskilled laborers; they included skilled workers, such as window glass workers. Nevertheless, opponents of contract workers claimed that capitalists conducted large scale importations of “ignorant, servile, unskilled, and debased labor,” or “‘pauper labor’ of Europe.”

Negative sentiment against contract laborers led to President Chester A. Arthur signing a bill that became known as the Foran Act on February 26, 1885. The Foran Act, also called the “alien contract labor law,” was named after its sponsor, Martin A. Foran, a former labor leader and a U.S. representative from Ohio. The act prohibited individuals and companies from prepaying, assisting, or encouraging the immigration of contract workers in other words, foreigners immigrating under contracts agreements to work in the United States and its territories. The law soon was amended in 1888 to begin deporting foreign contract workers already in the country.

In 1891, Congress went a step further by integrating these restrictions on contract workers into general immigration law, which administered the entry and removal of all foreigners, except the Chinese, whose immigration was restricted by Chinese exclusion laws. The Immigration Act of 1891 added contract workers to the list of prohibited groups of foreigners, including people likely to become public charges, people with contagious diseases, people with mental illness, and criminals.

Central to arguments in favor of the Foran Act was a view of imported workers as unfree, degraded workers, comparable to enslaved people. Proponents of the Foran Act argued that contract workers were unfree people in that their employers controlled them from the moment of their arrival in the United States. Foran argued that contract workers were “not freemen . . . . they are virtually the slaves of those greedy corporations who bring them here.” Forced into “the struggle for existence” over employment, many Americans would be replaced by “these foreign serfs.”

He thus presented the bill as an antislavery measure to protect American workers from competition with unfree labor imported from abroad. In a nation that abolished chattel slavery just two decades ago after the Civil War, opposition to a type of labor that seemed to resemble slavery was a powerful argument.

Labor leaders also stressed that as unfree people, contract workers did not come to the U.S. voluntarily; instead they were induced to migrate by capitalists. These workers, as Foran claimed, “do not initiate their coming.” Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), advanced the binary between free and unfree immigrants, declaring that he had no objection to immigration, so long as “they come here of their own free will.”

These perceptions of contract workers were built upon the existing racist idea that Chinese immigrants to the United States were “coolies,” or unfree indentured workers. Similar views applied to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, whom many Americans regarded as poor, uneducated, and inferior. Even though many immigrant workers were imported from Belgium, England, Germany, and Ireland, labor leaders predominantly critiqued Italian and Hungarian immigration, blaming capitalists for importing “as so many cattle, large numbers of degraded, ignorant, brutal Italian and Hungarian laborers.” As the San Francisco Call expressed, the condemnation was soon extended to the importation of “destitute Japanese pauper laborers.”

The criticism of labor importation acquired new phrases by the turn of the 20th century. Opponents of contract workers denounced their immigration induced or assisted by employers an transportation companies working with them as “artificial” or“unnatural” immigration.

The AFL resolved to oppose “all artificially stimulated immigration” and demanded “absolute prohibition of the landing of all contract and assisted emigrants.” In 1901, the congressional Industrial Commission on immigration condemned “the artificial immigration induced by employers for the purpose of breaking labor organizations.” Special immigration inspector Marcus Braun claimed that “we are burdened with a dangerous and most injurious unnatural immigration.”

During the first two decades of the 20th century, the Commissioner-General of Immigration, the head of the federal Bureau of Immigration, constantly used such terms as “artificial,” “unnatural,”and “stimulated” immigration disapproving of the importation of contract workers.The implication was clear that “natural” immigration, or the immigration of free people coming to the U.S. on their own, would be more desirable, and better suited to American life. Indeed, during the making of the alien contract labor law, Foran argued that “the best class of immigrants come” from England, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany, while Italy and Hungary sent contract workers to the United States. By the early 20th century, “unnatural” immigration was more commonly associated with immigration from southern and eastern Europe, Asia, and Mexico.

Herein lies one origin of the binary framework of immigration discourse in the United States today which divides noncitizens into “illegal aliens” and legal immigrants. The critique of contract workers created the ideas of natural and unnatural immigration, so that contract workers, or unnatural immigrants, could be vilified and their exclusion justified through contrast with the opposite category, free and natural immigrants. The debate over imported labor and the implementation of the Foran Act laid some of the discursive foundations for today’s debates by helping create a context in which immigration was discussed in dichotomous terms.

Ultimately, the distinction between natural and unnatural immigration remained murky in practice. Officials used their own discretion to decide what contract or assistance meant, often to the disadvantage of migrant groups they considered undesirable. Most immigrants whom they excluded as contract workers were coming to the United States voluntarily, and even those joining their U.S.-based family members could be labeled as contract workers. The binary categorization served as a tool to vilify some foreigners as unnatural immigrants and justify their exclusion.

Today, the category of the “illegal alien” has similar functions. It stigmatizes Latinx migrants, regardless of their immigration status, and legitimizes radical and inhumane approaches to border policing, while immigration restrictionists use it in expansive ways to inaccurately include lawful asylum seekers.

Regarding the migrants sent to Guantánamo Bay, the Trump Administration has not provided sufficient proof of their status and criminality. But reporting by ProPublica and Texas Tribune indicates that at least some of those sent to Guantanamo Bay had no criminal record at all, and many are, by the Trump Administration’s own declarations “low risk.” In fact, some of the people Guantanamo Bay can not even be labeled as unauthorized immigrants, because they entered the U.S. lawfully.

Categorization has been one of the fundamental problems, and the most unreliable ideas, in U.S. immigration policy. The words, labels, or categories that lawmakers use to describe different immigrant groups shape public support or disapproval. Those labels, however, are often arbitrary and do not match the realities of the groups, to the detriment of the immigrants and the rule of law itself.

Diaspora

11 Killed, 14 Injured in Mass Shooting at South African Hostel

11 Killed, 14 Injured in Mass Shooting at South African Hostel

At least 11 people, including a three-year-old child, have been killed in a mass shooting at a hostel in Saulsville township, west of Pretoria, South Africa’s capital.

Police spokesperson Brigadier Athlenda Mathe said three unidentified gunmen stormed the premises around 4:30am on Saturday and fired “randomly” at a group of people who were drinking.

A 12-year-old boy and a 16-year-old girl were also among the dead.

Mathe confirmed that 25 people were shot in total, with 14 others wounded.

No arrests have been made, and the motive for the attack remains unclear.

Authorities described the venue as an “illegal shebeen,” noting that many mass shootings in the country occur in such unlicensed liquor spots.

Police shut down 12,000 illegal outlets between April and September and arrested more than 18,000 people nationwide.

South Africa continues to battle soaring violent crime.

According to UN data, the country recorded a murder rate of 45 per 100,000 people in 2023–24, while police statistics show that 63 people were killed daily between April and September.

Diaspora

Benin Foils Military Coup Attempt, 14 Arrested

Benin Foils Military Coup Attempt, 14 Arrested

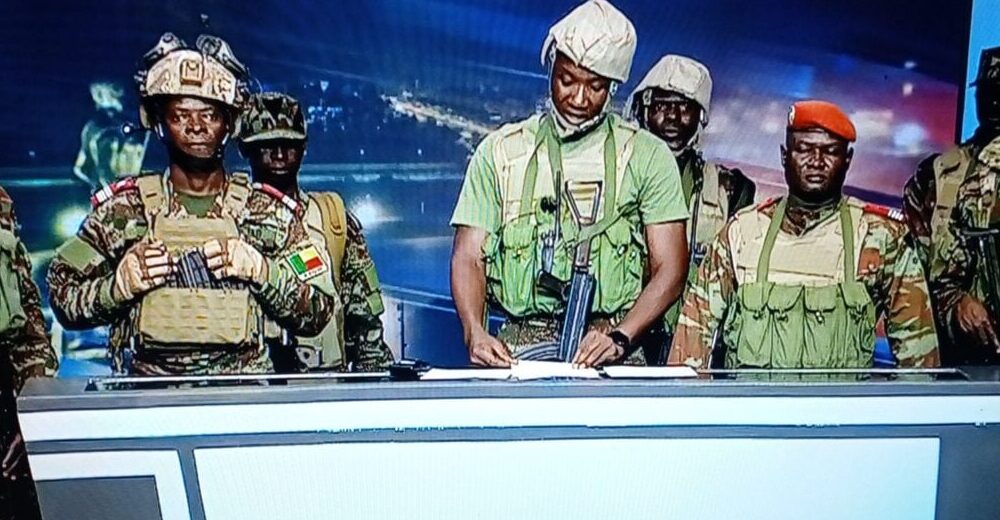

The government of Benin says it has thwarted an attempted coup after a group of soldiers tried to seize power in the early hours of Sunday.

Interior Minister Alassane Seidou, in a televised address, said the armed forces “remained committed to the republic” as loyalist troops moved swiftly to suppress what he described as “a mutiny aimed at destabilising the state and its institutions.”

Earlier, the renegade soldiers, led by Lt-Col Pascal Tigri, briefly took over the national television station and announced that President Patrice Talon had been removed.

It was reported that gunfire erupted near the presidential residence in Porto-Novo, while journalists at the state broadcaster were held hostage for several hours.

A presidential adviser later confirmed that Talon was safe, dismissing rumours that he had sought refuge at the French embassy.

French diplomats also denied the reports.

Government spokesperson Wilfried Leandre Houngbedji told Reuters that 14 people had been arrested so far.

A journalist in Cotonou said 12 of those detained were involved in storming the TV station, including a previously dismissed soldier.

The attempted takeover triggered heavy security deployment across Cotonou, with helicopters hovering overhead and major roads cordoned off.

Foreign embassies, including those of France, Russia, and the United States, issued advisories urging citizens to stay indoors.

In their broadcast, the rebel soldiers accused Talon of neglecting worsening insecurity in northern Benin, where militants linked to Islamic State and al-Qaeda have carried out deadly attacks near the borders with Niger and Burkina Faso.

They also protested rising taxes, cuts to public healthcare, and alleged political repression.

President Talon, 67, who came to power in 2016 and is expected to leave office next year after his second term, has faced growing criticism over democratic backsliding, including the barring of key opposition figures and recent constitutional amendments.

Sunday’s events add to a worrying pattern of military takeovers across West Africa, with recent coups in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Niger, and, just last week, Guinea-Bissau.

Ecowas, the AU, and Nigeria have all condemned the attempted coup in Benin, calling it a threat to regional stability.

Nigeria described the failed plot as a “direct assault on democracy” and commended Benin’s security forces for protecting the constitutional order.

Diaspora

Killings in Nigeria: ‘Enough is Enough,’ SNG-USA Cries Out from U.S. Capitol

Killings in Nigeria: ‘Enough is Enough,’ SNG-USA Cries Out from U.S. Capitol

By Boniface Ihiasota, USA

The Save Nigeria Group USA (SNG-USA) has intensified calls for urgent international action to halt what it described as a full-scale genocide against Christians in Nigeria.

Its President, Stephen Osemwegie, led a major rally at the U.S. Capitol Grounds in Washington, D.C., drawing Nigerians, Americans, clergy, human rights advocates and members of the diaspora to stand in solidarity with victims of violence.

Addressing the crowd in frigid weather, Osemwegie said millions of Christians across several Nigerian states live under constant threat of attacks.

He detailed a series of atrocities, including beheaded pastors, torched churches, abducted women and children, razed villages and wiped-out communities, insisting that the violence had long surpassed communal clashes and now represented a coordinated effort to annihilate Christian populations.

He cited the recent abduction of more than 300 pupils of Saint Mary’s Catholic School as evidence of the systematic nature of the attacks.

Osemwegie accused the Nigerian government of failing to uphold its constitutional responsibility to protect citizens, describing the 1999 Constitution as “a document imposed by soldiers” that had created a centralized system empowering extremists while weakening regional autonomy and endangering minority communities.

He called for a return to a constitutional framework similar to that of 1960, which he said would restore balanced governance and empower regions to safeguard their people.

The SNG-USA president commended U.S. President Donald J. Trump for redesignating Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern (CPC), praising him for moral clarity and willingness to act when others remained silent.

He urged the U.S. Government to enforce the designation fully, including sanctions, visa restrictions, and asset freezes against individuals, officials, and networks allegedly involved in terror financing, mass displacement, or the concealment of atrocities.

Osemwegie also called on U.S. Senate and House leadership to act with urgency, warning that every delay could cost more lives.

He appealed to Senate Republican Leader John Thune to advance Senator Ted Cruz’s legislation targeting violent extremist groups and their sponsors, and urged House Speaker Mike Johnson to move forward with resolutions formally recognising the killings of Christians in Nigeria as genocide.

He further demanded the release of thousands of pages of FBI documents allegedly related to criminal investigations involving Nigeria’s President, stressing that transparency was essential for both American and Nigerian interests.

Highlighting the case of Sunday Jackson, a Christian farmer reportedly sentenced to death for defending his community from attacks, Osemwegie said the situation reflected a justice system in which “killers walk free while defenders face execution.”

He emphasised that the movement was driven by conscience and divine instruction, and vowed that the group would continue to speak for the voiceless and defend the persecuted.

Following the rally, SNG-USA issued a statement reaffirming its position and thanking American political leaders for engaging with the group.

It expressed appreciation to Donald Trump for considering its appeals, to Senators Thune and Ted Cruz for their leadership, and to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Congressmen Riley Moore and Chris Smith for meeting with its delegation.

The group also offered condolences to Congressman Moore and the people of West Virginia over the deaths of recently fallen members of the West Virginia National Guard.

The statement revealed that senior officials of the U.S. Department of State held a two-hour closed-door meeting with SNG-USA representatives, during which survivors of attacks provided firsthand testimonies.

The organisation expressed optimism about the State Department’s willingness to listen and commitment to global religious freedom.

SNG-USA also acknowledged U.S. media outlets for hthe crisis. It thanked clergy, human rights organisations, Nigerian-American communities, and other supporters who participated in the rally despite freezing temperatures.

Osemwegie concluded by pledging that the group would remain resolute until justice is served, the killings stop, and displaced Christians are restored to their homes. He declared, “We will not stop until the genocide ends.”

-

Diaspora1 week ago

Diaspora1 week agoKillings in Nigeria: ‘Enough is Enough,’ SNG-USA Cries Out from U.S. Capitol

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSecurity Concerns: Ribadu Hosts U.S. Congressional Delegation in Abuja

-

Analysis1 week ago

Analysis1 week agoBeyond A Defence Minister, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

Diaspora1 week ago

Diaspora1 week ago11 Killed, 14 Injured in Mass Shooting at South African Hostel

-

Analysis1 week ago

Analysis1 week agoPerennial Coups in Africa, by Boniface Ihiasota

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCARICOM Hails Peaceful, Credible Conduct of Saint Lucia General Elections