Opinion

When Mercy Betrays Justice, by Boniface Ihiasota

When Mercy Betrays Justice, by Boniface Ihiasota

Presidential pardon is meant to be a sacred act — an instrument of compassion used sparingly to correct excesses of the law or ease human suffering. But in Nigeria, it often mutates into a political favour that undermines justice rather than serving it.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s recent exercise of clemency — which reportedly included drug barons and Maryam Sanda, convicted of killing her husband — has provoked deep national outrage. It raises a fundamental question: is the Nigerian presidency using mercy to uphold justice, or to reward privilege?

Under Section 175 of the 1999 Constitution, the President has the power to pardon or commute sentences upon the advice of the Council of State. But constitutional power does not translate to moral righteousness. Mercy must be anchored on fairness, transparency, and moral justification — none of which have been evident in this latest gesture.

The case of Maryam Sanda stands out like a bruise on the conscience of the nation. Convicted in 2020 for the gruesome murder of her husband, Bilyamin Bello, Sanda’s trial was thorough, her conviction upheld through due process. Her sudden pardon, reportedly influenced by family intervention, reeks of class privilege and political influence. It sends a dangerous message — that the wealthy and well-connected can always negotiate their way out of justice.

Even more troubling is the inclusion of convicted drug traffickers. At a time when the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) is battling to dismantle narcotics syndicates, the Presidency’s pardon of drug offenders undermines years of painstaking enforcement. It emboldens traffickers and discourages officers who risk their lives to keep the country safe.

This is not the first time Nigeria’s leaders have abused the prerogative of mercy. In 2013, President Goodluck Jonathan’s pardon of Diepreye Alamieyeseigha, the ex-Bayelsa governor convicted of corruption, drew global condemnation. It tainted Nigeria’s anti-graft image and emboldened those who see public office as a licence to loot.

The consequences of such indiscriminate pardons are dire. They erode public trust in the judiciary, demoralise judges who labour for years to deliver justice, and delegitimise the rule of law. When presidential pens can nullify judicial rulings overnight, justice becomes negotiable — a commodity for the powerful.

Across the world, the abuse of clemency has produced similar consequences. In South Korea, repeated presidential pardons for convicted ex-presidents Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak sparked nationwide protests, forcing lawmakers to debate curbing the practice. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro’s politically motivated pardon of a far-right ally convicted for attacking the Supreme Court was condemned as an attack on democracy.

In Peru, the 2017 pardon of former dictator Alberto Fujimori, who was serving time for human rights abuses, triggered mass protests and international backlash, forcing courts to overturn the pardon two years later. In South Africa, early releases of politically connected individuals in the name of “national healing” have often deepened public cynicism and distrust in government institutions.

Even in the United States, where presidential pardons are common, the process attracts intense scrutiny. Barack Obama’s clemency programme focused on non-violent drug offenders serving disproportionate sentences. Each pardon was documented publicly to ensure fairness. By contrast, Donald Trump’s pardons of political allies and campaign donors drew sharp criticism, raising concerns of corruption and cronyism.

Nigeria, however, lags behind global accountability standards. The Presidential Advisory Committee on Prerogative of Mercy operates in secrecy. The public is rarely informed of the criteria or rationale for pardons. Were the convicts reformed? Were they victims of judicial error? Or were they simply politically connected? Without transparency, clemency becomes a mockery of justice.

Yet, clemency itself is not the problem. When properly used, it can heal wounds, decongest overcrowded prisons, and give reformed offenders a second chance. In Canada, for instance, pardons (called record suspensions) are carefully reviewed, excluding violent crimes and ensuring public safety. In Germany, presidential pardons are extremely rare and only considered under compelling humanitarian grounds.

Nigeria can learn from these systems. Clemency should prioritise prisoners of conscience, the terminally ill, and those unjustly convicted — not murderers and drug traffickers. The National Assembly should urgently review the constitutional process to introduce transparency, public disclosure, and limits on eligible offences.

Crimes like murder, terrorism, drug trafficking, and grand corruption should not qualify for presidential mercy except under extraordinary humanitarian grounds. A pardon should not erase accountability; it should reflect reform and remorse. Anything less erodes the moral fibre of justice.

Beyond legality, the ethical question looms large: what happens when mercy becomes selective? Thousands of ordinary Nigerians languish in prisons for petty offences, many without trial for years. They are the forgotten souls who deserve presidential mercy — not those whose connections can bend the system.

The late Justice Chukwudifu Oputa once said, “Justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done.” Today, justice in Nigeria is neither seen nor done when presidential mercy is dispensed like patronage.

History shows that unchecked clemency corrodes institutions. If Nigeria continues down this path, we risk normalising injustice and undermining the credibility of our judiciary. The rule of law must remain the ultimate arbiter, not the whims of political benevolence.

Presidential mercy should be a balm for the broken — not a shield for the powerful. To forgive without fairness is to betray the very soul of justice. And when justice becomes negotiable, a nation’s conscience is no longer intact.

Analysis

Time to Defend Every Nigerian Life, by Boniface Ihiasota

Time to Defend Every Nigerian Life, by Boniface Ihiasota

Nigeria stands today at a moral and historical crossroads, one that demands clear-eyed reflection and courageous action. From the vantage point of the diaspora, with the benefit of distance yet the burden of deep emotional connection, it is impossible to ignore the painful realities unfolding across parts of the Middle Belt and the North. Communities that once lived in harmony now grapple with waves of violence often described with soft, almost technical language — “herder-farmer clashes,” “bandit attacks,” “reprisal killings.”

Behind these labels are fathers and mothers who can no longer return to their farms, children who sleep in fear, elders watching the erosion of traditions that once bound communities together, and families who have endured losses no words can fully capture. These are Nigerians — Christians, Muslims, farmers, herders, artisans, all deserving of dignity and safety.

This crisis is not simply a security failure. It is a moral test of our nationhood. In the diaspora, we encounter societies where public safety, community trust, and national cohesion are not abstract aspirations; they are supported by deliberate, well-funded systems. These systems are not perfect, but they offer models Nigeria can adapt in practical, culturally grounded ways.

And while the statistics on Nigeria’s challenges are sobering, they point not to government guilt, but to the urgent need for coordinated, transparent, data-driven reforms that protect vulnerable communities and rebuild public confidence.

Reports cited by global faith-monitoring organisations, humanitarian groups, and rights bodies present a troubling picture. One frequently referenced dataset in international discourse, including the 2024 World Watch List, places Nigeria among countries where Christians face severe risks, with figures running into the thousands for those reported killed in 2023 alone.

Parliamentary briefings abroad and humanitarian groups such as the Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust have documented recurring attacks, widespread displacement, and systematic destruction of villages. Other organisations, such as Intersociety, also chronicle patterns of violence affecting both Christians and Muslims in rural regions. While some of these figures remain contested within Nigeria, they nevertheless reinforce the urgency of strengthening national protection systems and ensuring that every Nigerian, irrespective of faith or ethnicity, is afforded equal security, equal justice, and equal empathy.

From a diaspora viewpoint, what stands out is not just the scale of the violence but the preventable nature of many tragedies. Advanced countries facing communal tensions have invested in strong early-warning networks, multi-agency coordination mechanisms, and community-centred policing models.

These systems show measurable success by improving response times, reducing escalation, and fostering trust between citizens and security institutions. Nigeria can draw practical lessons from these approaches. Effective national coordination models, such as those used in the United States for crisis management, rely on unified command structures, common communication standards, and the integration of faith-based and community organisations into emergency planning.

A Nigerian adaptation of this model could create a national platform where security agencies, traditional rulers, faith leaders, and civil society jointly analyse threats, share intelligence, and mobilise rapid responses. Such a structure, rooted in Nigeria’s cultural realities but informed by global best practices, would save lives.

Equally important is community policing, not the informal, unregulated kind that fuels abuse or vigilantism, but structured, accountable, measurable partnership policing. Countries like the UK and Canada demonstrate that when local security actors operate with clear legal boundaries, training, and oversight, citizen trust and intelligence flow improve dramatically. Nigeria can replicate this by formally integrating vetted community groups and traditional institutions into local security frameworks under police supervision. This approach respects the local knowledge that rural communities possess while ensuring professional accountability.

Security, however, is only one dimension. The human cost of the violence like displacement, destroyed livelihoods, psychological trauma requires a level of social investment that advanced nations routinely prioritise.

International health bodies highlight that conflict exposure significantly heightens long-term mental health needs. Nigeria will require expanded trauma care, community counselling programs, and accessible psychosocial support delivered through primary healthcare and faith networks. Rebuilding homes, restoring farms, and providing tools and training are equally essential; these interventions not only restore dignity but also deepen trust in government.

Places of worship, too often targeted, need structured protection. Advanced countries have implemented national schemes that support security upgrades for mosques, churches, synagogues, and temples most at risk. Nigeria can create a similar framework in high-risk regions, providing basic infrastructure like lighting, reinforced entry points, and community safety training. Such measures demonstrate state commitment to protecting freedom of worship, a constitutional right and a moral obligation.

As the diaspora, we recognise the efforts the Nigerian government has already made in confronting insurgency and upgrading security architecture. But the next phase requires deliberate attention to vulnerable rural populations in flashpoint areas like Plateau, Benue, and Southern Kaduna. These regions are not peripheral; they are central to Nigeria’s food security, interfaith cohesion, and national stability. Protecting them is both a justice imperative and a strategic necessity.

The path forward must be one of collaboration, not division. Churches and mosques must champion narratives of unity. Civil society must monitor data transparently. Media must avoid sensationalism and focus on verified information. Security agencies must be commended when they act swiftly and fairly, and held accountable when they fall short. Government must demonstrate openness, empathy, and partnership. And the diaspora must continue to contribute technical expertise, advocacy, and resources.

Nigeria has survived darker moments and emerged stronger. With decisive leadership, evidence-based reforms, and a renewed commitment to the sanctity of every Nigerian life, this tragedy can be transformed into an opportunity for national rebirth. The time for blame is over. What Nigeria needs now is compassion anchored in facts, courage backed by action, and collaboration driven by a shared belief that every Nigerian deserves to live and worship without fear.

Analysis

As G20 Moves On Without America, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

As G20 Moves On Without America, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

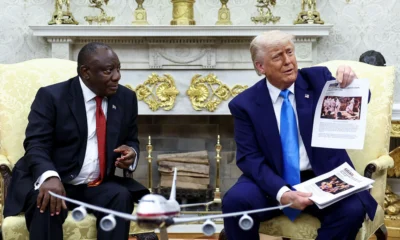

When the G20 summit convened this November in Johannesburg, the first time the gathering has ever been held on African soil, one seat was starkly empty. The world’s largest economy, the Donald J. Trump-led United States, simply refused to attend. No president, no senior envoy, not even a delegation. The absence was louder than any diplomatic communiqué, a void that hung over the proceedings like an unspoken challenge.

For weeks before the summit, Trump had telegraphed the boycott. He announced that no U.S. official would participate, calling it “a total disgrace” that the gathering was being hosted in South Africa. He justified the walkout with allegations that Pretoria was enabling abuses against its white-minority Afrikaner community and presiding over land seizures and a supposed “white genocide”—claims widely rejected within South Africa and dismissed by many global observers. Still, he held to his stance, ensuring that the United States would be missing from the table it once dominated.

Yet the empty chair did not halt the summit. Far from it. When the doors closed and the work began, more than forty countries and organisations had confirmed their participation. According to South Africa’s foreign-affairs minister, a total of forty-two delegations were registered: twenty G20 member states (excluding the U.S.), sixteen invited guest nations, and six representing regional economic blocs across Africa, the Caribbean and East Asia. It was one of the most diverse gatherings in the forum’s history.

Of the twenty G20 member states, a clear majority sent their heads of state or government. Four countries opted for high-level substitutes: Russia, Mexico and Argentina sent their foreign ministers or equivalents, while China was represented by its Premier rather than President Xi Jinping. Apart from these deviations and the complete American boycott, the turnout remained strong. At least sixteen G20 countries had their top leadership present, a level consistent with or even above several previous summits.

The question, then, is what this moment signifies—for the G20, for Africa’s place in global governance, and for a world increasingly shaped by fractured geopolitics.

The symbolic dimension is impossible to ignore. For decades the United States has been the gravitational centre of global economic coordination, the anchor whose participation guaranteed that G20 pronouncements could be translated into global action. Without Washington in the room, many of the traditional levers of influence like financial stability mechanisms, trade dynamics, institutional power felt looser and less predictable. The absence introduced doubt: could the G20 still claim to be the premier platform for steering the global economy if its most powerful member stayed away? Some analysts wondered whether the forum’s future was in jeopardy.

Yet paradoxically, the boycott created breathing space. Instead of collapsing under the weight of American non-participation, the summit moved forward with surprising cohesion. Leaders adopted a 122-point declaration issued unusually on the summit’s opening day that centred on climate action, debt sustainability, energy transition and global inequality. These were not peripheral concerns but core priorities, particularly for developing economies. And critically, they reflected Africa’s agenda far more directly than in past years.

For Africa, a continent long relegated to the fringes of global decision-making, the Johannesburg summit brought a subtle but significant shift. It marked a moment where issues that have shaped African suffering and aspiration, unsustainable debt, climate vulnerability, access to green energy, development finance were not treated as charity cases or footnotes but as global imperatives. South Africa’s leadership in shaping the agenda was evident: it shepherded conversations that placed the continent not as a crisis zone but as a partner with agency.

Even the ending of the summit carried symbolism. The traditional handover of the G20 presidency, typically marked by the passing of a wooden gavel from one host to the next, did not unfold in its usual choreography. President Cyril Ramaphosa brought the meeting to a close with a strike of the gavel, but there was no American official to step forward and receive the ceremonial baton. The moment underscored the deeper reality: the world’s most powerful nation had chosen absence in a year when Africa chose presence.

Naturally, this raised concerns. If powerful states begin treating multilateral forums as optional, depending on domestic politics or ideological sentiments, the foundations of global governance weaken. The G20 has played central roles in navigating financial crises, stabilising commodity markets, coordinating pandemic responses and mobilizing climate finance. A precedent where a superpower boycotts the summit could encourage similar behaviour by others in future moments of crisis. The potential ripple effects on global trust, crisis management and economic coordination are worrying.

But Johannesburg also demonstrated that the G20 is more adaptable than its critics assume. Instead of paralysis, the summit produced consensus. Instead of division, it surfaced shared interests. And instead of waiting for the United States to validate decisions, countries across continents showed that cooperation was still possible, even necessary, without America’s guiding hand.

For many African nations, this sense of possibility was palpable. For years, they have been the subjects of global policies drafted in distant capitals. In Johannesburg, they felt more like contributors. The declaration reflected structural concerns that matter from Lagos to Nairobi: access to concessional finance, green industrialization, fair energy transition pathways, investment in resilience rather than repeated cycles of vulnerability. These were not afterthoughts but central pillars.

Still, optimism should remain grounded. Declarations alone do not build roads, transition energy grids or relieve debt burdens. They do not shift the voting power held by wealthy nations in global financial institutions. And they do not erase the influence the United States wields over the IMF, World Bank and other structures that control the flow of global capital. Even in absence, Washington’s shadow is long.

At the same time, the boycott raises uncomfortable questions about the future. If summits can be walked away from because of domestic political narratives or ideological disagreements, the global architecture becomes more fragile. Future crises, whether debt shocks, pandemics, food shortages or climate-induced disasters require collaboration and not boycotts. A forum that can be abandoned sets troubling precedents.

Yet this moment may also become a hinge in history. Not because it solves everything, but because it marks a shift in rhythm. It shows the system bending, under pressure, toward greater inclusion. It proves that Africa can host, convene and even lead. More than nineteen members signed the declaration; voices from the Global South resonated with unusual clarity. And for once, those who are often asked to wait for the powerful to decide had already begun making decisions of their own.

For Nigeria, the implications are profound. The global conversation is moving toward issues that directly affect its development path: debt restructuring, climate resilience, green industrial transformation, food security and transparent governance. Nigeria must engage with these shifts deliberately. Declarations will mean little if national policy fails to align with them. The country needs bold investments in climate adaptation, expanded support for agriculture and manufacturing, improved fiscal management and stronger accountability mechanisms. Its diaspora and civil society have roles to play as watchdogs, advocates and bridges linking global promises to local action.

The United States will remain central in global affairs. Its currency, markets and institutional power ensure that. But the Johannesburg summit demonstrated something important: relevance in the G20 is no longer solely measured by presence. Sometimes absence reshapes the conversation more than participation. The empty chair at Johannesburg was not just a diplomatic symbol; it became a catalyst for rethinking old assumptions.

The challenge now is to ensure that the space created by that absence is not wasted. The real measure of success will lie in implementation in whether climate justice initiatives become real funding pipelines, whether debt deals become fairer, whether green energy investments materialise, and whether global decisions begin to reflect the needs of people from Kenya to Ghana, rather than only those in United States or Germany. It will lie in whether African leaders rise to the occasion, using the moment to insist on equity rather than settling for symbolism.

The world watched as the G20 pressed on, limping perhaps, but moving. And Africa did more than host; it spoke, it influenced, it guided. If Nigeria and the rest of the continent seize the momentum, the reverberation of that gavel strike in Johannesburg could echo not only through global institutions but through local communities seeking fairness and development.

In the end, the empty seat left behind by the United States did not define the summit. The G20 may not have needed America to agree on a declaration in 2025. But building a future that transcends absence will require a different kind of presence.

If Africa answers that call, history may yet record that the empty chair marked not a failure, but the beginning of something new.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

Analysis

Our Schoolgirls Again? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Our Schoolgirls Again? By Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

They have taken our daughters again. Another school, another night raid, another round of shock and condemnation delivered from our politicians both in Abuja and Birnin Kebbi. The latest tragedy in Maga, Kebbi State, where armed men stormed the Government Girls Comprehensive Secondary School in the dead of night, killed a vice-principal and abducted about twenty-five schoolgirls returns Nigeria to a familiar, unbearable question: why does this keep happening?

The attack, like so many before it, was swift, brutal, and predictable. Two of the girls escaped hours later, but the others were marched away into the dark bush, swallowed by the expanding geography of kidnapping that now defines northern Nigeria’s insecurity.

Since Chibok in 2014, Nigeria has lived in cycles of outrage, promises, search-and-rescue operations, whispered negotiations and quiet retreats. Governments change, uniforms change, spokespersons change, but the pattern remains what it has always been: repeating national grief wrapped in official denial.

In my column this week, I attempt what the Nigerian state has struggled to do by cataloguing this grim history, examine the policies proclaimed to address it and identify the failures that persist, including logistics and political evasions that have enabled this tragedy to endure.

The starting point is Chibok. In April 2014, 276 girls were taken from their hostels in Borno State in an operation that exposed the fragility of Nigeria’s security architecture. Boko Haram swept into the school with ease, herded the girls away, and vanished into Sambisa Forest. Dozens escaped or were released through negotiations, but many remain unaccounted for. Those images of grieving parents, empty metal bunks and students forced into trucks at gunpoint became an international symbol of Nigerian state failure.

Four years later, Dapchi happened. In February 2018, 110 girls were taken by another faction of Boko Haram. Weeks later, most of them returned in a convoy of insurgents who reportedly apologised to locals. Five girls died in captivity and one girl, Leah Sharibu, was held back allegedly for refusing to renounce her faith. The government denied ransom payments, but independent reports and community testimonies suggested that a financial or negotiated settlement was part of the release. As with Chibok, the truth remains tucked beneath layers of state secrecy.

By 2021, the epicenter of school abductions had shifted from the northeast to the northwest, where criminal gangs labelled “bandits” for bureaucratic convenience discovered that abducting schoolchildren offered a profitable business model. In February of that year, around 279 girls were taken from Jangebe in Zamfara State. The girls were released days later in circumstances that raised more questions than answers, especially regarding whether the government had adhered to its public stance of never paying ransom. The official line was that the girls were freed through “peaceful negotiations,” a phrase that Nigerians have learned to interpret with skepticism.

Then came the Kuriga raid in Kaduna State in March 2024. Gunmen seized scores of pupils and staff, prompting a frantic response from soldiers and vigilantes. The kidnappers demanded one billion naira, a figure that reflects the industrialisation of kidnapping in Nigeria. The government later announced rescues and recoveries, but the opacity surrounding negotiations and whether payments were made reinforced public distrust. Kuriga demonstrated how deeply entrenched the kidnapping economy had become, and how state responses often came too late or too tentatively to deter future attacks.

Now Kebbi joins this ledger of heartbreak. The Maga abduction, which took place on 17–18 November 2025, is a reminder that no policy documents, no televised condemnations, no promises of “never again” have fundamentally changed the ground realities for children in rural Nigerian schools. The attackers struck with confidence, knowing full well that response times would be slow, the terrain favoured them, and the state’s first instinct would be to issue a condemnation rather than a deterrent.

To understand the persistence of this crisis, we must examine the architecture of government responses. Each administration, from Goodluck Jonathan to Muhammadu Buhari to Bola Tinubu, has followed a familiar script. First comes loud condemnation, then high-level visits by ministers and security chiefs, then a declaration of intensified operations. Afterward, either the abductees reappear through rescue or release or they fade from media attention until the next tragedy.

In 2021, Nigeria released a National Policy on Safety, Security and Violence-Free Schools. On paper, it is an impressive document: it outlines minimum standards, coordination structures, and the responsibilities of federal, state and local governments to secure educational spaces. It is complemented by Nigeria’s earlier endorsement of the Safe Schools Declaration in 2015, an international pledge to protect education during conflict. But policies are not the same as implementation. Despite these commitments, most rural schools in the north still lack perimeter fencing, adequate lighting, trained security personnel, reliable communication systems or rapid-response mechanisms. The majority operate like soft targets, predictable, poorly defended, and accessible.

The logistics failures are basic and persistent. Attackers favour schools that are isolated, under-lit, and often undefended at night. They use motorcycles and pickup trucks that can navigate forest paths better than the armoured vehicles of Nigerian troops. Communication gaps delay alerts, while coordination problems between police, military and community vigilantes often lead to confusion rather than rapid mobilisation. In some cases, parents reach the school before security forces do.

The deeper problem is that the economics of kidnapping favour the criminals. Ransom payments whether officially acknowledged or not have become a major source of revenue for both insurgent groups and bandit gangs. Investigative reporting has alleged that millions of euros were exchanged in the negotiations that secured the release of some Chibok girls in 2017. The government denied the claims, but cannot provide transparent evidence to the contrary. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, compiled estimates suggested that over 3,600 people were kidnapped nationwide and around five billion naira was paid in ransoms. In an environment where ransom remains profitable and risks for perpetrators remain minimal, the incentives favour repetition. Children thus become economic assets in the underworld of Nigerian insecurity.

The Kebbi abduction fits this pattern. While kidnappers had not publicly stated their demand at the time of writing, the trajectory of past incidents shows that negotiations and financial incentives inevitably become part of the conversation. Communities already fear that the girls may be ransomed or exchanged for safe passage, even as officials continue to insist that government “does not pay ransom.”

The question, then, is what should Nigeria do differently? The first step is transparency. If the government ever pays ransom, openly or through intermediaries, it must be recorded, audited and overseen by a parliamentary mechanism. Denial has become a policy crutch that hides failures and permits the kidnapping economy to thrive. Citizens are not asking for operational details but for honest accounting. Democracies cannot manage national security challenges with secrecy as default.

The second step is to build a national school-security system that actually works. This requires ring-fenced funding, independent audits, and yearly progress reports. School security cannot be left to states alone, many of which are broke or conflicted by local politics. Fencing, lighting, guard recruitment, communication devices and training must be budgeted as essential infrastructure, not as emergency responses after tragedies.

Third, Nigeria must rethink its over-militarised approach. The presence of soldiers in a state does not automatically translate into safer schools. What works is community-integrated policing, properly trained rural response units, early-warning systems, and consistent policing presence around high-risk schools. Military raids may free hostages but rarely prevent the next abduction.

Fourth, the government must confront the ransom market directly. Either Nigeria adopts a strict no-ransom policy that is enforced transparently and consistently, or it acknowledges that negotiations are sometimes unavoidable and establishes a regulated oversight process. The current situation, denials masking back-channel payments is the worst of both worlds.

Finally, the nation needs public, verifiable data. Nigerians should be able to know how many schools have met minimum safety standards, how much has been spent on safe-school measures since 2014, how many perpetrators have been prosecuted, and how often early-warning systems have actually worked. Without measurement, improvement is impossible.

At the heart of this crisis is a moral dilemma. If the state refuses to pay ransom, captives may remain in the bush indefinitely. If the state pays ransom secretly, it fuels the market and endangers future generations. The choice requires honesty, not political performance.

The Kebbi abduction is not merely a news event; it is a national reckoning. Each time children are taken, Nigeria replays the same tragedy with the same official lines and the same institutional weaknesses. The country does not need more condemnations. It needs functioning fences, radios that work at midnight, guard training that is monitored, and a government that tells the truth about what it spends and what it pays.

If Nigeria continues down this path where policies exist on paper but not on the ground, where the kidnapping economy thrives in the shadows, where the security of schoolchildren depends on luck rather than system, then the question “Our Schoolgirls again?” will soon become an annual lament. It does not have to be this way. But to break the cycle, Nigeria must embrace transparency, discipline, and the mundane, unglamorous work of prevention.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoInsecurity: US Spy Plane Begins Operations in Nigeria

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoTinubu Sends 32 Additional Ambassadorial Nominees to Senate for Confirmation

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoUS Shooting Sparks Controversy Over Afghan Vetting as Trump Blames Biden

-

Analysis6 days ago

Analysis6 days agoAs G20 Moves On Without America, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoIsraeli PM Netanyahu Seeks Presidential Pardon Amid Ongoing Corruption Trials

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoUS–South Africa Rift Deepens Over G20 Boycott and Diplomatic Snubs