Analysis

As G20 Moves On Without America, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

As G20 Moves On Without America, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

When the G20 summit convened this November in Johannesburg, the first time the gathering has ever been held on African soil, one seat was starkly empty. The world’s largest economy, the Donald J. Trump-led United States, simply refused to attend. No president, no senior envoy, not even a delegation. The absence was louder than any diplomatic communiqué, a void that hung over the proceedings like an unspoken challenge.

For weeks before the summit, Trump had telegraphed the boycott. He announced that no U.S. official would participate, calling it “a total disgrace” that the gathering was being hosted in South Africa. He justified the walkout with allegations that Pretoria was enabling abuses against its white-minority Afrikaner community and presiding over land seizures and a supposed “white genocide”—claims widely rejected within South Africa and dismissed by many global observers. Still, he held to his stance, ensuring that the United States would be missing from the table it once dominated.

Yet the empty chair did not halt the summit. Far from it. When the doors closed and the work began, more than forty countries and organisations had confirmed their participation. According to South Africa’s foreign-affairs minister, a total of forty-two delegations were registered: twenty G20 member states (excluding the U.S.), sixteen invited guest nations, and six representing regional economic blocs across Africa, the Caribbean and East Asia. It was one of the most diverse gatherings in the forum’s history.

Of the twenty G20 member states, a clear majority sent their heads of state or government. Four countries opted for high-level substitutes: Russia, Mexico and Argentina sent their foreign ministers or equivalents, while China was represented by its Premier rather than President Xi Jinping. Apart from these deviations and the complete American boycott, the turnout remained strong. At least sixteen G20 countries had their top leadership present, a level consistent with or even above several previous summits.

The question, then, is what this moment signifies—for the G20, for Africa’s place in global governance, and for a world increasingly shaped by fractured geopolitics.

The symbolic dimension is impossible to ignore. For decades the United States has been the gravitational centre of global economic coordination, the anchor whose participation guaranteed that G20 pronouncements could be translated into global action. Without Washington in the room, many of the traditional levers of influence like financial stability mechanisms, trade dynamics, institutional power felt looser and less predictable. The absence introduced doubt: could the G20 still claim to be the premier platform for steering the global economy if its most powerful member stayed away? Some analysts wondered whether the forum’s future was in jeopardy.

Yet paradoxically, the boycott created breathing space. Instead of collapsing under the weight of American non-participation, the summit moved forward with surprising cohesion. Leaders adopted a 122-point declaration issued unusually on the summit’s opening day that centred on climate action, debt sustainability, energy transition and global inequality. These were not peripheral concerns but core priorities, particularly for developing economies. And critically, they reflected Africa’s agenda far more directly than in past years.

For Africa, a continent long relegated to the fringes of global decision-making, the Johannesburg summit brought a subtle but significant shift. It marked a moment where issues that have shaped African suffering and aspiration, unsustainable debt, climate vulnerability, access to green energy, development finance were not treated as charity cases or footnotes but as global imperatives. South Africa’s leadership in shaping the agenda was evident: it shepherded conversations that placed the continent not as a crisis zone but as a partner with agency.

Even the ending of the summit carried symbolism. The traditional handover of the G20 presidency, typically marked by the passing of a wooden gavel from one host to the next, did not unfold in its usual choreography. President Cyril Ramaphosa brought the meeting to a close with a strike of the gavel, but there was no American official to step forward and receive the ceremonial baton. The moment underscored the deeper reality: the world’s most powerful nation had chosen absence in a year when Africa chose presence.

Naturally, this raised concerns. If powerful states begin treating multilateral forums as optional, depending on domestic politics or ideological sentiments, the foundations of global governance weaken. The G20 has played central roles in navigating financial crises, stabilising commodity markets, coordinating pandemic responses and mobilizing climate finance. A precedent where a superpower boycotts the summit could encourage similar behaviour by others in future moments of crisis. The potential ripple effects on global trust, crisis management and economic coordination are worrying.

But Johannesburg also demonstrated that the G20 is more adaptable than its critics assume. Instead of paralysis, the summit produced consensus. Instead of division, it surfaced shared interests. And instead of waiting for the United States to validate decisions, countries across continents showed that cooperation was still possible, even necessary, without America’s guiding hand.

For many African nations, this sense of possibility was palpable. For years, they have been the subjects of global policies drafted in distant capitals. In Johannesburg, they felt more like contributors. The declaration reflected structural concerns that matter from Lagos to Nairobi: access to concessional finance, green industrialization, fair energy transition pathways, investment in resilience rather than repeated cycles of vulnerability. These were not afterthoughts but central pillars.

Still, optimism should remain grounded. Declarations alone do not build roads, transition energy grids or relieve debt burdens. They do not shift the voting power held by wealthy nations in global financial institutions. And they do not erase the influence the United States wields over the IMF, World Bank and other structures that control the flow of global capital. Even in absence, Washington’s shadow is long.

At the same time, the boycott raises uncomfortable questions about the future. If summits can be walked away from because of domestic political narratives or ideological disagreements, the global architecture becomes more fragile. Future crises, whether debt shocks, pandemics, food shortages or climate-induced disasters require collaboration and not boycotts. A forum that can be abandoned sets troubling precedents.

Yet this moment may also become a hinge in history. Not because it solves everything, but because it marks a shift in rhythm. It shows the system bending, under pressure, toward greater inclusion. It proves that Africa can host, convene and even lead. More than nineteen members signed the declaration; voices from the Global South resonated with unusual clarity. And for once, those who are often asked to wait for the powerful to decide had already begun making decisions of their own.

For Nigeria, the implications are profound. The global conversation is moving toward issues that directly affect its development path: debt restructuring, climate resilience, green industrial transformation, food security and transparent governance. Nigeria must engage with these shifts deliberately. Declarations will mean little if national policy fails to align with them. The country needs bold investments in climate adaptation, expanded support for agriculture and manufacturing, improved fiscal management and stronger accountability mechanisms. Its diaspora and civil society have roles to play as watchdogs, advocates and bridges linking global promises to local action.

The United States will remain central in global affairs. Its currency, markets and institutional power ensure that. But the Johannesburg summit demonstrated something important: relevance in the G20 is no longer solely measured by presence. Sometimes absence reshapes the conversation more than participation. The empty chair at Johannesburg was not just a diplomatic symbol; it became a catalyst for rethinking old assumptions.

The challenge now is to ensure that the space created by that absence is not wasted. The real measure of success will lie in implementation in whether climate justice initiatives become real funding pipelines, whether debt deals become fairer, whether green energy investments materialise, and whether global decisions begin to reflect the needs of people from Kenya to Ghana, rather than only those in United States or Germany. It will lie in whether African leaders rise to the occasion, using the moment to insist on equity rather than settling for symbolism.

The world watched as the G20 pressed on, limping perhaps, but moving. And Africa did more than host; it spoke, it influenced, it guided. If Nigeria and the rest of the continent seize the momentum, the reverberation of that gavel strike in Johannesburg could echo not only through global institutions but through local communities seeking fairness and development.

In the end, the empty seat left behind by the United States did not define the summit. The G20 may not have needed America to agree on a declaration in 2025. But building a future that transcends absence will require a different kind of presence.

If Africa answers that call, history may yet record that the empty chair marked not a failure, but the beginning of something new.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

Analysis

Now That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

Now That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

In December 2025, Nigeria’s Senate confirmed Lateef Kayode Are as the ambassador-designate, only that where he will be posted to was unknown. Just a few days ago, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu through his spokesperson, Bayo Onanuga announced that he would be posted to the United States of America, ending a prolonged leadership vacuum across major Nigerian diplomatic missions.

For Nigerians living in the diaspora, particularly in the U.S., this development carries significant political, economic and strategic implications. The absence of a substantive ambassador in Washington, D.C., for more than two years had not only weakened Nigeria’s official voice in U.S. policy circles but also limited high-level advocacy on issues directly affecting Nigerians abroad—from visa policies to trade and investment ties.

Nigerians in the United States form one of the largest African-born communities in the country. Official data indicates roughly 393,000 foreign-born Nigerians reside in the U.S., making them one of the most educated and professionally active diaspora groups. Over 60 % hold bachelor’s degrees or higher, with many working in healthcare, technology, education and finance.

Other estimates suggest the broader Nigerian diaspora in the U.S. might be closer to 750,000 people, when including Nigeria-born and U.S.-born descendants who actively engage in both nations’ social, cultural and economic life. This community is not just a demographic cluster; it is a powerful reservoir of expertise and networks that can bridge the two countries.

Economically, the Nigerian diaspora plays a crucial role in Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings. In 2024, official remittances from Nigerians abroad reached $20.93 billion, more than four times the value of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the country during the same period. Such remittance flows are second only to crude oil in terms of foreign exchange inflow and accounted for a major stabilising support to Nigeria’s external accounts.

Given the scale of these flows, the Nigerian government and its diplomatic mission must pay greater attention to policies that make remitting easier, safer and more cost-effective. Recent discussions in the U.S. about proposed taxes on remittances to countries like Nigeria signalled potential challenges to these inflows, underlining the need for strong diplomatic engagement to protect economic interests.

In addition to remittances, U.S.–Nigeria bilateral trade remains robust, with total trade estimated at around $13 billion. This figure reflects deep economic interdependence—American energy firms, technology companies, and investors have interests in Nigeria’s energy and digital sectors, while Nigerian exports continue to find strong markets in the U.S.

Diplomacy is more than numbers. With a resident ambassador, Nigeria can more effectively advance strategic interests in areas such as education exchanges, technology partnerships, and security cooperation. The U.S.–Nigeria relationship already includes formal mechanisms like the U.S.–Nigeria Binational Commission (BNC) and the Commercial and Investment Dialogue, which cover development, governance, and economic opportunities.

A permanent ambassador strengthens Nigeria’s hand in these dialogues and ensures that policy decisions made in Washington reflect an accurate picture of Nigeria’s realities and priorities. This matters especially in areas like visa policies, professional mobility, and legal protections for Nigerians living and working in the U.S.

For many Nigerians living abroad, the practical functions of an embassy matter deeply—passport renewals, legal assistance, and consular support in times of crisis hinge on a mission that has the authority and clout to act. A long-standing absence of an ambassador meant that much of this work was handled by chargés d’affaires who lack the full mandate to negotiate broader policy solutions.

Having a full ambassador provides continuity, visibility, and influence. It reassures diasporans that their government cares about their welfare and is committed to protecting their rights and contributions in the host country.

Beyond services, the diaspora wants a Nigerian foreign policy that sees them as partners in development, not just sources of remittances or cultural ambassadors. Nigerians in the U.S. are entrepreneurs, researchers, policymakers, and educators who invest not just money but ideas back home. The new ambassador should leverage that intellectual capital and help create channels through which diaspora skills and networks can be systematically integrated into Nigeria’s economic and technological growth agenda.

Now that Nigeria has a U.S. ambassador-designate, it must shift from symbolic representation to strategic engagement. The ambassador must be visible, accessible and proactive—bringing diaspora voices into policy conversations, advocating for fair treatment of Nigerians abroad, and expanding economic and cultural ties that benefit both nations.

For the diaspora, this appointment is not just good news—it is an opportunity to deepen influence, strengthen identity, and build bridges that realize the promise of a more dynamic Nigeria on the world stage.

Analysis

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

The Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

There are pains that refuse to be edited out of memory. No matter how carefully one chooses words, some experiences bleed through the page, heavy and unyielding. I write this not merely as a columnist accustomed to weighing public issues, but as a father whose pen now trembles under the weight of a personal loss that should never have happened.

The death of my eight-month-old daughter, Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman, is not just a private tragedy; it is a mirror held up to a system that looks impressive on the surface but collapses at the moment it is most needed.

On Friday, 23rd January 2026, my daughter was taken to General Hospital Suleja because she was unable to suck breast properly. It did not appear, at first, to be a death sentence. Like many parents, I trusted the judgment of trained professionals. The hospital itself inspired confidence. It is well renovated, neatly structured, and visually reassuring. From the outside, it looks like what a modern government hospital should look like. That appearance, in truth, persuaded me to use it. I believed, as any reasonable citizen would, that a facility that looks ready must surely be ready.

That belief became my greatest regret.

Rahmah was admitted the same day on the claim that her condition required emergency attention. She was taken into the Emergency Pediatric Unit, a designation that suggests urgency, speed, and competence. But what followed was neither urgent nor competent. For over thirteen hours, my daughter lay there in visible discomfort, struggling, crying faintly, weakening by the minute.

During this entire period, no doctor came to see her. The only available doctor was contacted several times by a Nurse. Calls were made. Messages were sent. Appeals were raised. Yet she never showed up, never examined the child, never intervened until she passed away Saturday night.

It is difficult to explain what it feels like to watch a child suffer while help remains just out of reach. Hospitals are supposed to be sanctuaries of hope, places where time matters and minutes are counted with seriousness. But in that Emergency Pediatric Unit in Suleja General Hospital, time became an enemy. Thirteen hours passed like a slow execution.

At some point, sensing danger, I requested that my daughter be transferred to a private hospital. I was ready to bear any cost. That request was not granted. Instead, oxygen was administered, as though oxygen alone could replace diagnosis, treatment, and medical presence. Oxygen became a gesture, not a solution. Sadly, when Rahmah took her last breath, it was not because her condition was incurable. It was because care was absent.

This is where the agony deepens. This was not a dilapidated structure abandoned by government. This was a renovated hospital, one that fits neatly into budget speeches and commissioning photographs. Niger State, since 2023, has consistently announced significant allocations to the health sector. In the 2024 fiscal year, over forty billion naira was earmarked for health, with emphasis on improving facilities, upgrading hospitals, and strengthening service delivery.

In 2025 and into the proposed 2026 budget, health allocations rose even higher, approaching over seventy billion naira, according to official budget presentations. These figures are not rumours; they are public records. They are read aloud in legislative chambers and celebrated in press releases. Yet, standing beside my dying child, those billions meant nothing.

A hospital is not healed by paint, tiles, and glass alone. A renovated building without doctors is like a body without a pulse. General Hospital Suleja may look functional, but inside, it suffers from a shortage that is far more dangerous than cracked walls. The absence of medical personnel, especially during emergencies, is a silent killer. No amount of renovation compensates for a system where doctors can choose not to respond to repeated calls when the needs arise.

Also strangely to me, there is the issue of power. What kind of hospital functions with generator power for barely three hours a day, typically between 8pm and 11pm? In a medical environment, power is not a convenience; it is life itself. Equipment depends on it. Monitoring depends on it. Emergency response depends on it. When power becomes a luxury, care becomes compromised. It is disturbing that in 2026, parents still have to pray for electricity in a government hospital while budgets worth billions are announced yearly.

What hurts most is not just the loss, but the realization that this suffering was avoidable. It was not fate. It was negligence. It was indifference. It was a system that has mastered the art of looking prepared while remaining dangerously hollow.

As a columnist, I have written about governance failures, policy gaps, and institutional decay. I have used statistics and official statements to interrogate power. But nothing prepares you for the moment when those abstract failures become personal. When the child you named, carried, and loved becomes a casualty of the same system you once critiqued from a distance.

I cannot, in good conscience, advise even my enemy to use that hospital again, not because it looks bad, but because looks deceive. The pain of trusting a fine exterior only to encounter fatal emptiness inside is something I would not wish on anyone. Health facilities should not be deceptive showpieces. They should be living systems, staffed, powered, responsive, and humane.

This is not a call for sympathy. It is a demand for honesty. If governments will continue to announce impressive budgets, then citizens deserve impressive outcomes. If hospitals are renovated, they must also be manned. If emergency units exist, they must function as emergencies, not waiting rooms for death. Accountability must move beyond paperwork and reach the ward, the night shift, the unanswered phone call.

Alabidun Rahmah AbdulRahman was eight months old. She was my only daughter. She deserved more than silence, more than delay, more than oxygen without care. She deserved a doctor who would show up.

Some losses change a man forever. This one has changed my writing. The pen is no longer just a tool of commentary; it is now an instrument of mourning and witness. If this column unsettles those who read it, then perhaps it is doing what hospitals like General Hospital Suleja failed to do that day — respond with urgency.

For my daughter, and for every child whose life depends on more than painted walls and budget speeches, this agony must be written, remembered, and acted upon.

Analysis

In Honour of Our Fallen Heroes, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

In Honour of Our Fallen Heroes, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

Every nation is sustained by the quiet courage of those who stand between order and chaos. In Nigeria, that burden has rested heavily on the shoulders of the Armed Forces and other security personnel for decades, but especially in the past fifteen years of relentless insecurity. From the creeks of the Niger Delta to the forests of North West and North East to the highways of the North Central, Nigerian soldiers, airmen, sailors and policemen have borne the brunt of a war that is often unseen by those who sleep peacefully at night. To speak in honour of our fallen heroes is not merely to rehearse grief; it is to confront, honestly and courageously, the meaning of sacrifice, the demands of honour and the moral obligation of welfare owed to those who gave everything and to the families they left behind.

Nigeria’s contemporary security challenges did not begin yesterday. The Boko Haram insurgency, which escalated violently after 2009, has remained one of the deadliest conflicts on the African continent. According to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), tens of thousands of lives have been lost to the insurgency, with security personnel accounting for a significant proportion of the casualties. Names like Giwa Barracks, Baga, Monguno and Marte are etched into the collective memory of the military not just as locations, but as reminders of intense battles where many soldiers paid the supreme price. One such name that still resonates is Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Abu Ali, a gallant armoured corps officer who was killed in action on 4 November 2016 near Malam Fatori in Borno State while leading troops against Boko Haram fighters. His death symbolised the kind of front-line leadership that defines true military honour: commanding from the front, sharing risks with subordinates, and refusing the safety of distance.

Beyond the North East, the expanding frontiers of insecurity have claimed more lives. On 29 June 2022, Nigeria was shaken by the deadly ambush in Shiroro Local Government Area of Niger State, where at least 34 soldiers were killed by bandits while on a stabilisation mission. The scale of that single loss was a sobering reminder that the battlefield had shifted, and that sacrifice was no longer confined to one theatre of operation. Similar tragedies have followed. In March 2024, 17 soldiers lost their lives in Okuama community, Delta State, during a peace mission gone wrong, prompting national outrage and renewed debates about rules of engagement, intelligence failures and community-military relations. Each of these incidents added fresh names to a growing roll of honour, while also raising uncomfortable questions about preparedness, equipment and support for those sent into harm’s way.

Yet, sacrifice is not only measured in deaths. Thousands of Nigerian service personnel have returned from operations with life-altering injuries, trauma and scars that are invisible but enduring. The Defence Headquarters has repeatedly acknowledged the psychological toll of prolonged deployments, particularly in counter-insurgency operations where lines between combatants and civilians are blurred. The fallen heroes, therefore, represent not only those who died, but also those whose lives were irreversibly changed in service to the nation. To honour them meaningfully is to recognise that sacrifice is cumulative, personal and often lifelong.

Honour, however, must not be reduced to rhetoric. Every 15th of January, Nigeria observes Armed Forces Remembrance Day (now Armed Forces Celebration and Remembrance Day), a tradition rooted in the commemoration of soldiers who died in the First and Second World Wars and later expanded to include those lost in peacekeeping missions and internal security operations.

On 15 January 2026, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu through Vice President Kashim Shettima laid a wreath at the National Arcade in Abuja and reaffirmed the nation’s gratitude to its fallen heroes, describing them as “the pillars upon which our peace rests.” Similar ceremonies took place across states, from Lagos to Enugu, Kaduna to Kwara, accompanied by solemn words and military parades. These rituals matter. They reaffirm national memory and signal state recognition. But honour loses meaning if it ends at symbolism.

True honour is institutional and continuous. It is reflected in how promptly families of the fallen are informed, how respectfully remains are handled, how transparently benefits are processed and how consistently promises are kept. Over the years, allegations of delayed entitlements and neglected widows have surfaced, sometimes fuelling public anger and mistrust. The Nigerian Army and the Ministry of Defence have responded by clarifying welfare frameworks and insisting that official policies are robust. According to the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Defence, families of deceased service members are entitled to death benefits, gratuity, pensions, burial expenses and payments under the Group Life Insurance Scheme, a statutory policy that mandates life insurance coverage for all public servants, including military personnel.

In October 2023, President Tinubu approved an assurance policy valued at about ₦18 billion to cover life insurance benefits for fallen heroes, reinforcing the administration’s stated commitment to military welfare. In March 2024, the federal government also bestowed posthumous national honours on the 17 soldiers killed in Delta State, alongside promises of housing support and educational scholarships for their children. Several state governments have complemented federal efforts. Lagos State has sustained its scholarship scheme for children of fallen officers, while Ogun, Edo and other states have publicly pledged financial and social support to bereaved families during recent remembrance events.

These measures are commendable, and fairness demands that government be acknowledged where it has taken concrete steps. Welfare frameworks today are more clearly articulated than they were a decade ago, and there is greater public scrutiny of how military benefits are administered. Nonetheless, the test of honour lies not in policy documents but in lived experience. A widow who waits years for entitlements, or a child of a fallen soldier who drops out of school due to lack of support, represents a moral failure that no wreath-laying ceremony can erase. Honour must therefore be defended daily through efficient institutions, accountable processes and humane engagement with those who bear the cost of loss.

The argument for improved welfare is not sentimental; it is strategic. Nations that neglect the families of their fallen undermine morale among serving personnel. Soldiers who see that the state stands firmly by its promises fight with greater confidence and commitment. Conversely, perceived neglect breeds cynicism and erodes trust. Nigeria’s security challenges demand motivated, professional and resilient forces, and welfare is a critical pillar of that resilience. This is why calls by veterans’ groups, civil society organisations and commentators for continuous review of military welfare policies should not be dismissed as noise. They are part of a necessary civic conversation about national priorities.

There is also an ethical dimension that transcends strategy. The social contract between the state and its defenders is unique. When a citizen in uniform dies in service, the state inherits a moral responsibility to the dependants left behind. This responsibility does not expire with news cycles or budgetary constraints. It endures across administrations and economic fluctuations. In many ways, how a nation treats its fallen heroes’ families is a mirror of its values.

To be clear, honouring fallen heroes does not mean glorifying war or romanticising death. It means acknowledging the harsh realities of service and committing to reduce avoidable losses through better intelligence, equipment, training and leadership. It also means ensuring that when loss does occur, it is met with compassion, justice and sustained support. Sacrifice should never be cheapened by neglect, nor should honour be diluted by inconsistency.

As Nigeria continues to confront insecurity in multiple forms, the roll call of fallen heroes reminds us that peace is neither abstract nor free. It is paid for in blood, courage and broken families. To write in their honour is to insist that remembrance must translate into responsibility. The fallen cannot speak for themselves, but the living can speak through policies that work, institutions that care and a national conscience that refuses to forget. In doing so, Nigeria does not only honour its fallen heroes; it affirms the worth of every life pledged in defence of the nation.

Alabidun is a media practitioner and can be reached via alabidungoldenson@gmail.com

-

Analysis6 days ago

Analysis6 days agoThe Agony of a Columnist, by Alabidun Shuaib AbdulRahman

-

Analysis5 days ago

Analysis5 days agoNow That Nigeria Has a U.S. Ambassador-Designate, by Boniface Ihiasota

-

Diplomacy5 days ago

Diplomacy5 days agoCARICOM Raises Alarm Over Political Crisis in Haiti

-

News6 days ago

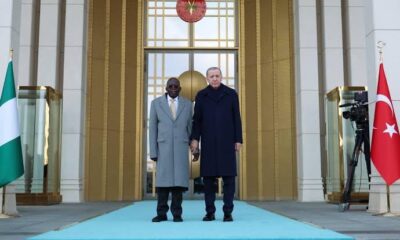

News6 days agoTinubu Unhurt After Brief Stumble at Turkey Reception

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMacron invites Chad’s Déby to Paris amid push to reset ties

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCourt, Congress Pile Pressure on DHS Over Minnesota Operations